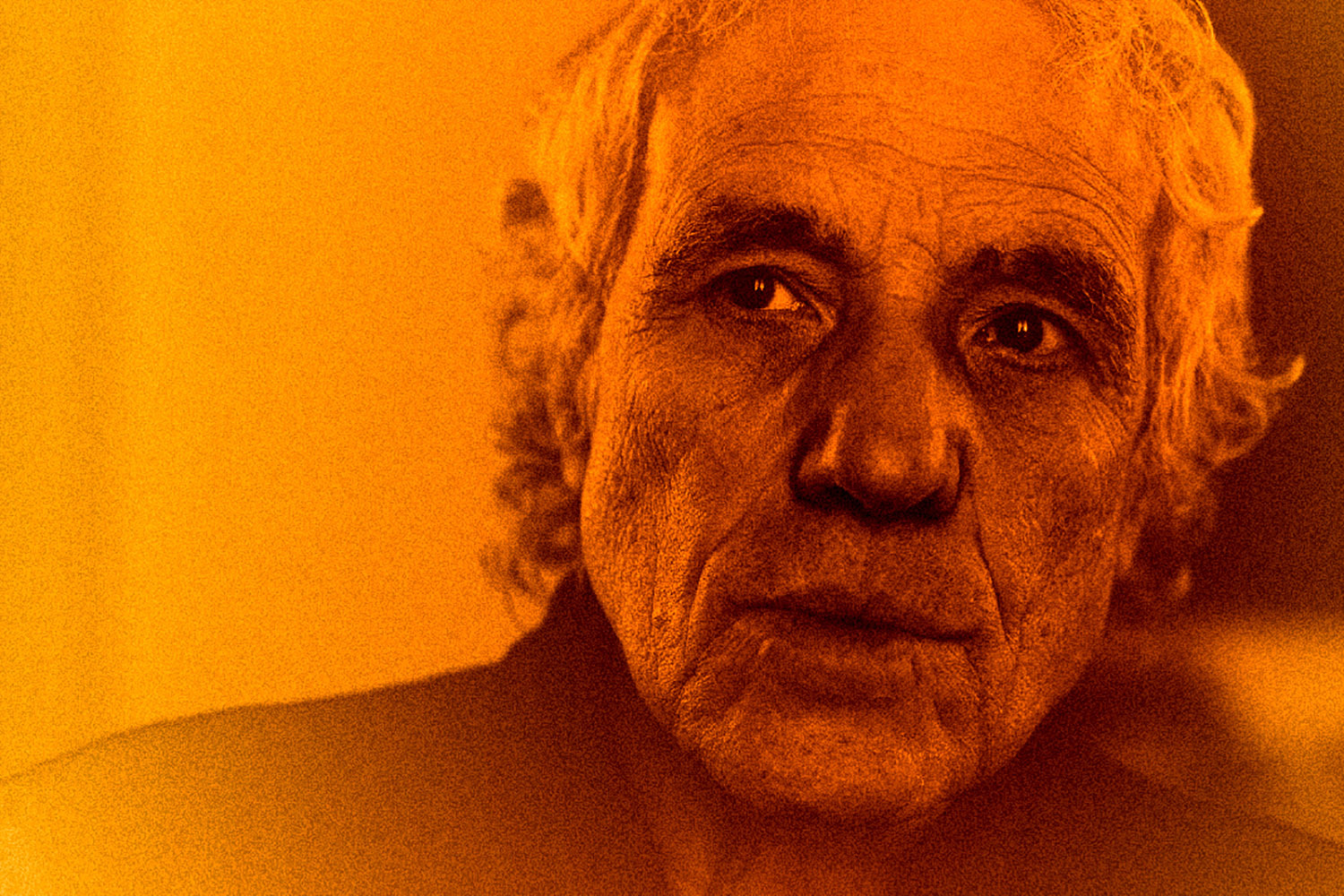

There’s an irksome little irony — in that sense, a perfectly apropos irony — that the quintessential Albert Brooks line doesn’t even come from one of the movies he made. It’s from Broadcast News, written and directed by no-relation James L. Brooks, in which the man born Albert Einstein netted an Oscar nomination as a scrupulous yet charisma-free reporter too clammily anxious to realize his dreams of romance or on-air anchoring. In a moment of impotent self-pity, the very sort that make it difficult for women to desire him, he sounds a cry to the heavens. “Wouldn’t this be a great world if insecurity and desperation made us more attractive?” he moans. “If ‘needy’ were a turn-on?”

The framing of that quote, a virtual mission statement for Albert Brooks as auteur, speaks volumes about how he views the world and his place in it. Everyone’s prone to the occasional bout of hopeless frustration about their own flaws, but it’s more often directed inward than outward. All too significantly, he does the opposite. His wish is not for confidence, or contentment, or self-assuredness. He knows people like that, guys like his nemesis Tom, the likable yet unintelligent newsreader commanding the network’s spotlight. That guy doesn’t even know how many positions are in the Presidential cabinet. Who wants to be happy? It would be more right and just for everything else to change, goes the petty reasoning of his aside.

The first five features that Brooks wrote and directed, now playing on the Criterion Channel in a handsome partial-career retrospective, more precisely chart the restless existential searcher’s path as he embodies, dissects and matures out of that solipsism. The real Brooks inhabited this mindset as naturally onscreen as he crafted it behind the scenes, and yet each film focused on the effort to transcend and live better, to put the Sisyphean labor broadly. Considering Criterion’s selections as a loose pentalogy, an audience can see him getting closer and closer to grasping his version of enlightenment. Which, by his relative standard, usually leaves him down in a slightly nicer, more livable sector of the dumps.

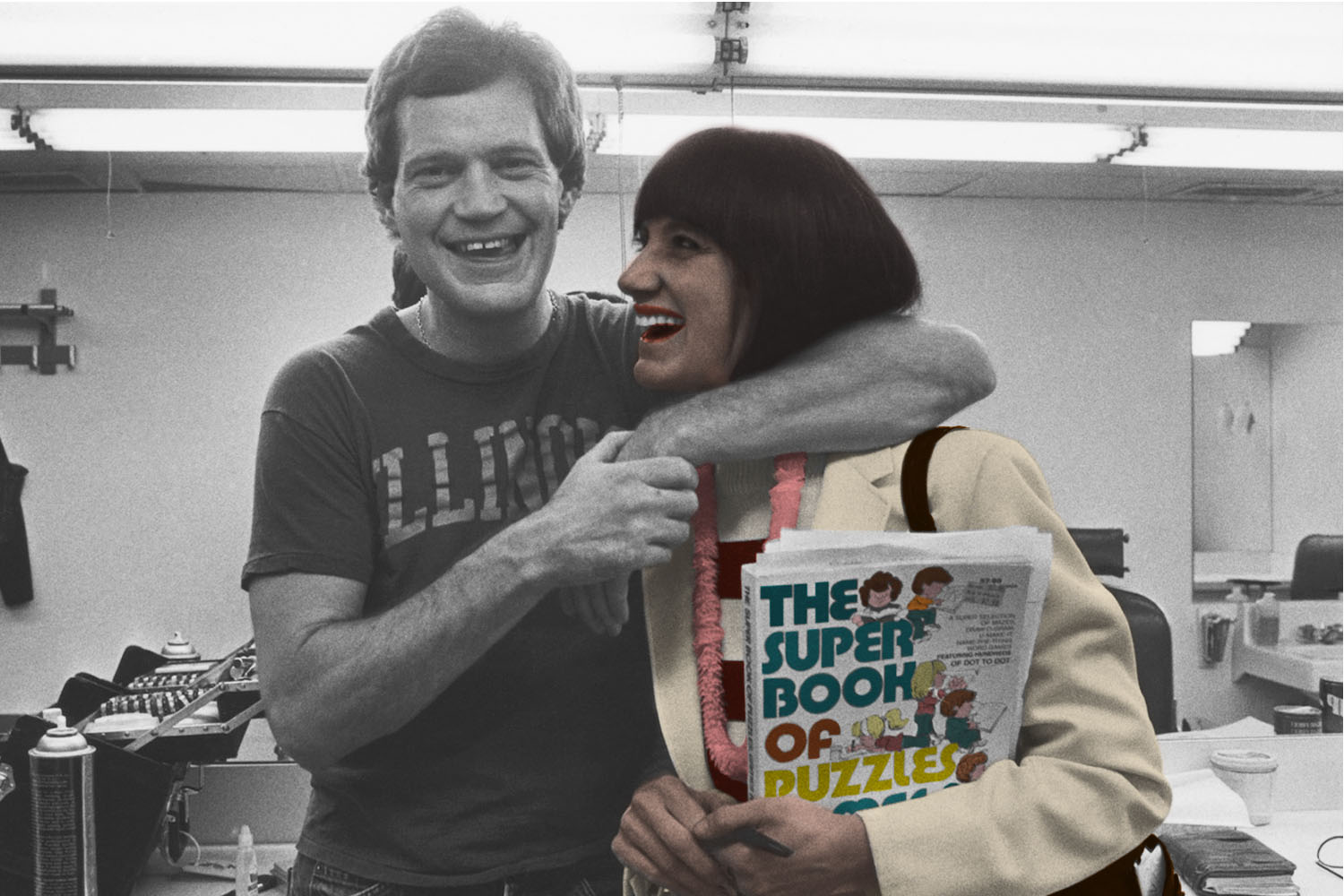

After cutting his teeth in TV with late-night appearances and Saturday Night Live shorts studied by comedy nerds with Talmudic dedication, a young Brooks brought a fresh, despairing perspective to his early work in Hollywood. His typical character was several shades more alienating than your average nebbish, jealous and cactus-prickly type, and neurotic to the point of narcissism. At the center of his being, he resents the unavoidable unfairnesses of adulthood, that maddening way that the less worthy seem to be constantly getting lucky breaks. He sees the defects of character that he’d rather make the new norm than improve as rational, the correct response to fortune’s vaunting of all things mediocre and hollow. Anyone with such a keen awareness of these cosmic imbalances would react the exact same way. Mostly in futility, he labors to impose order on a cruel universe, reconciling his vision of how things should be with the pesky reality that won’t stop intruding.

That’s the long and short of 1979’s Real Life, in which the preening, fatuous “Albert Brooks” persona first came out to play at cinemas. He portrayed an unflattering parody of himself in such televised bits as “Albert Brooks’ Famous School for Comedians” and the world’s worst ventriloquism routine, undercutting his purported showbiz know-how with incompetence, vanity and spiky sarcasm. That character would go on to fill a feature runtime in Real Life, his grandest endeavor, a documentary in the vein of the proto-reality TV landmark An American Family. Faux-Albert, a filmmaker, descends on the Yeagers of small-town Arizona like a hurricane, sensationalizing their day-to-day with his invasive, flagrantly unethical methods until their ranch-style abode has been engulfed in flames. Every step of the way, he tries to rig the game in order to create compelling drama, an early attempt to remake his surroundings in his own harebrained image. Like so many great tragicomedies before it, the script ends with “Albert” descending into madness, unable to make peace with all that falls outside his control as he frantically gins up an ending with suitable pizzazz.

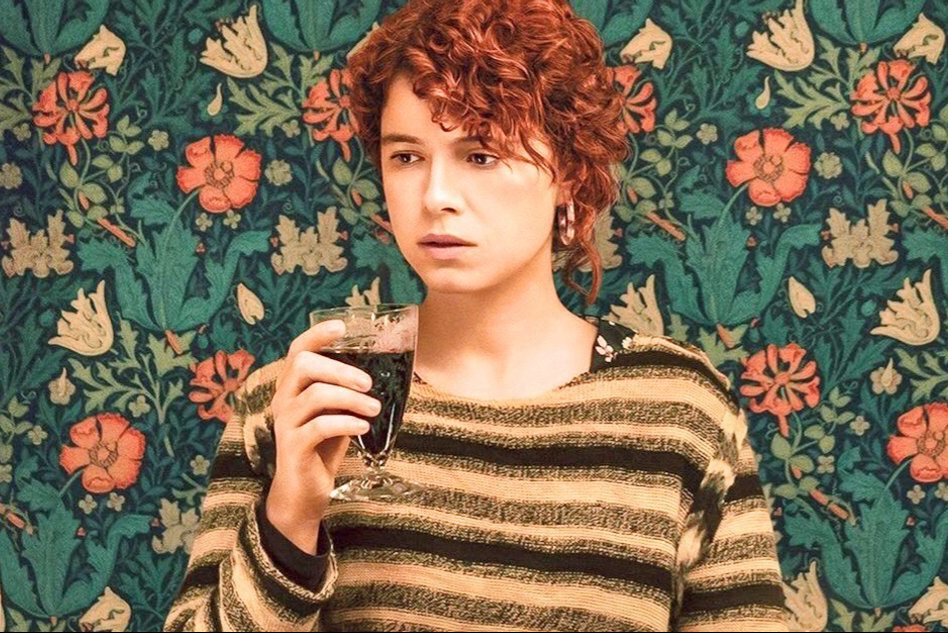

In the following two films, companion pieces in their nightmare views of dating and marriage, Brooks dealt himself more overtly fictive roles, nonetheless bringing him closer to Earth. 1981’s Modern Romance and 1985’s Lost in America begin with more grounded sorts of social experiments, though they inevitably push Brooks and anyone trapped in his orbit into the same extreme emotional register. In the former film, he’s a movie editor who decides to break up with his girlfriend (Kathryn Harrold) only to find that being single isn’t all it was cracked up to be, and that reconciliation may have passed him by. In the latter, he’s an upper-level corporate drone cajoling his wife (Julie Hagerty) into “dropping out” from polite society — like in Easy Rider, he constantly explains, a little more pathetic every time — and taking their $100,000 nest egg on the road. These films won over a slice of the viewing public for their uncompromising pessimism, as men verging on the contemptible repeatedly double down on the same mistakes in a bid at some personal liberation.

In both instances, however, he ends up right back where he started. In Modern Romance, Brooks’s character tries to treat his own relationship like the sci-fi film starring George Kennedy he tweaks into the shape of his choosing at work. But even after he convinces his ex to get back together out of his idealized memory of the time they shared, he sabotages himself once again with pathological envy, accusing her of cheating based primarily on snooping and paranoia. Whether love or hate, it’s all in his head. A wry post-script to the film informs us that after the credits finished rolling, the two of them continued splitting up and reuniting all but ad infinitum, as if determined not to learn anything from these experiences.

There’s a discouraging circularity to Lost in America as well, in which the yuppie’s own fakeness rudely awakens him from his fantasy of authenticity on the two-lane blacktop. The main couple never really abandon their precious creature comforts, and once they’ve lost it all through a series of screw-ups and bad breaks, they turn tail and head to New York to beg for the jobs they swore off. (In a flourish of delicious humiliation, reinstatement comes with a pay cut.) Brooks’s avatars kept defaulting back to the misery they know well enough to consider comfortable, and convincing themselves it’s for the best.

The breakthrough begins in 1991, with Defending Your Life and the most redemptive arc Brooks would ever allow one of his own characters. As in Lost in America, he plays another advertising executive, the lowliest of soul-sapping professions by Tinseltown calculus. This one’s dead, idling in a comically banal version of purgatory complete with all-you-can-eat buffets and bus schedules until he can be judged by an afterlife tribunal consigning him to heaven or hell. The high-concept setup puts itself in explicitly moral terms, with the growth that’s so long eluded the Brooks oeuvre now a do-or-die proposition. Without conceding to the syrupy sentiment his work has always staunchly opposed, he grants a reprieve: the hapless Daniel Miller taps into his courage following lifelong cowardice and saves himself, finding a healthier and more meaningful love with the virtuous Meryl Streep as he floats up to the celestial beyond. For the first time, a happily ever after doesn’t curdle into a fate worse than death.

He brought this evolved perspective with him to Mother in 1996, which inverts his usual approach to plot construction. The Brooks character, a frustrated sci-fi novelist coming off his second divorce, inserts himself into another set of circumstances designed to break him out of a rut. Except that the decision to move back in with his overbearing mother (Debbie Reynolds) demands that he give up control instead of exerting it, and comes from a place of therapeutic self-interrogation we’ve never seen in him before. He theorizes that revisiting the formative elements of his youth could illuminate his problems with women in the present, and while the film arrives at an overly tidy and prescriptive conclusion to that effect, it’s still a step forward developmentally. The film ends not with a resolution to hold on to everything holding him back, but with the choice to let it go in pursuit of a new beginning. He meets a woman at a gas station in the final scene, their courtship off to a more auspicious start now that our man has shed his baggage. Again, it’s all a bit clean, but it shows an artist moving past his younger self to advance creatively.

The trail laid out by these five films inspires hope in the sort of viewer inclined to favor Brooks’s films, which require that we at least sympathize with the strain of negativity he made his signature, if not totally relate. His hard-won realization that his grievances don’t make him wiser or superior, only tired and glum, suggests that a kindred spirit can make the same breakthrough. If it’s not too late for the man who once prayed for a world full of desperate neediness, it’s not too late for any of us.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.