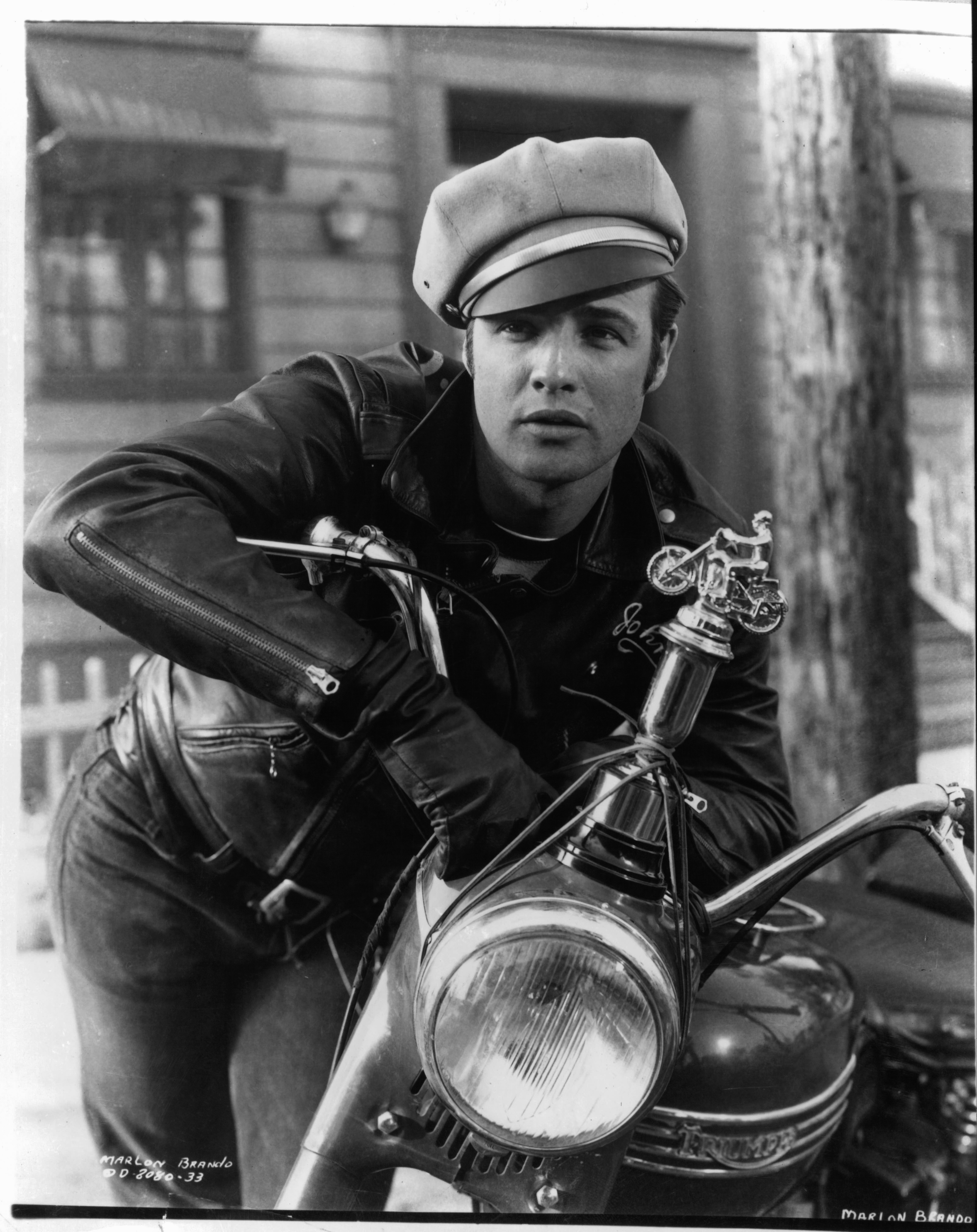

A lightbulb went off when artist Touko Laaksonen saw stills of Marlon Brando in The Wild One. The 1953 film features Brando as Johnny Strabler, leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club. In a black leather jacket and white T-shirt, jeans, boots and cap, Brando quickly became the visage of rebellion around the world: not just Eisenhower’s conservative, post-war America, but in Laaksonen’s native Finland as well.

Male sex appeal prior to that Brando moment had been limited to men in suits for the most part. Laaksonen found sexiness in the style and rebellious status of Brando’s Wild One garb, and it inspired him to perpetuate that clothing’s erotic potential. “There’s something to be said about sexy,” says Durk Dehner, who co-founded the Tom of Finland Foundation with Laaksonen. “When something is sexy, it doesn’t go away, it retains that kind of fortitude and nuance to it and I think that’s part of the magic of Tom’s fashion influence.” Though the illustrator passed in 1991, he celebrates his centenary this year, and with it his ongoing impact on the history of men’s fashion.

Laaksonen began committing his fantasies of men in uniform to paper while still a teenager and before he served in the Finnish Army, but promptly destroyed them upon being drafted in 1940. During the war, he embarked on numerous sexual encounters with soldiers on both sides of the war, Nazis and Allies, the memory of which became fodder for sexualized illustrations he made after the war. While he loathed the ideology of the Nazis who the Finns fought alongside during the war, Laaksonen loved their leather boots.

Homosexuality was illegal in Finland until 1971. So for the first half of his prolific careere, Laaksonen’s erotic work was done in secret. He learned how to photograph his models, develop film and print images, since he couldn’t very well take them to the local printer. By day he was an art director at international advertising agency McCann Erickson, now McCann, and he didn’t want to compromise his work there, either.

Laaksonen would continue to create what he called his “dirty drawings” through the 1950s, but they took on a new look after Brando’s Johnny Strabler appeared. What were once vibrant color gouache or pencil illustrations of men in brown leather jackets and cloth caps or army greens became strictly graphite. Black leather jackets, black boots and black jeans on rippling, lustfully swollen he-men. Though Laaksonen’s drawings typically feature especially well-endowed men performing most definitely not-suitable-for-work sex acts, there’s also an incredible attention paid to their clothing, and they are more often clothed than not. He was famous for saying “To me, a fully dressed man is more erotic than a naked one.” It shows in his work, all figures drawn with a careful precision evident in the creasing of leather, a button fly, a tilted hat, the pocket of a denim jean. Many of the designs in his images Laaksonen also created on his own.

“His bodies are going to be something that really also comes from the postwar era, the need to combat the idea of effeminacy of homosexuality,” says Dr. Adam Geczy, a senior lecturer in Visual Art at the University of Sydney and the co-author of the 2018 book Fashion and Masculinities in Popular Culture. The idea of the homosexual before the 1950s was only a highly effeminate one. While some gay men were (and remain) proudly effeminate, others wanted to be gay on their own terms, without having their identity prescribed to them. Laaksonen was among them, and drew the men he both desired and identified with. In doing so, he created a visual language for gay men that had previously been publicly unavailable to them, one where its actors were permitted to be masculine, happy and sexually dominant.

While his work has occasionally been criticized for conforming to masculine stereotypes, the extent to which it pushes, parodies and camps them is anything but straight. “It violates [stereotypical masculinity] by saying, ‘This is also ours, and we’re doing it better but we’re also sending it up,’” Geczy says. “It then creates a similar kind of gatekeeping on the straight male that was hitherto enclosed on the gay male.” It also creates the possibility of straight men aspiring to what Laaksonen shows as homosexual presentation. “What I really like about [Laaksonen’s work] now is that any straight boy would look at them and go, ‘Shit, I would love to have a body like that,’” Geczy says. “This is a powerful concept.”

It’s also worth noting that Laaksonen’s men were always working class: sailors, soldiers, construction workers, police officers and the like. Beginning with the Brando look, there became a subversiveness attached to working-class identification that Laaksonen’s work also adopted. “The Brando jacket is a version of a bomber jacket. The white T-shirt, that’s an undershirt, that’s underwear … [it’s] the generic, the makeshift, and a type of non-style. Jeans is the worker, jacket is the fighter, cap is dockyard worker and fighter in one. A series of signifiers that are using their origins in underclass and aggression, that’s the idea of needing to rebel,” Geczy says.

Laaksonen pushed the look to an extreme, and what Geczy describes as a relentless one at that. “He creates this proxy gay universe … a gay Olympus. Demigods. But the demigods have a different kind of heroism because they play fast and loose with class and using that idea of low-rent as a form of both access to difference but also as a kind of violation of the basic class hierarchies that are associated with heteronormative, post [imperialism].” Laaksonen’s work pushed this kind of ensemble so far into the sexual that the donning of it also became a signifier of sexuality itself.

Laaksonen had made his way into the American visual market in 1957, with drawings in and on the cover of Physique Pictorial, a homoerotic magazine that displayed nude bodybuilders under the guise of athletic modeling to avoid obscenity implications. He had simply signed the pictures “Tom” to avoid outing himself under his real name, and Physique Pictorial founder Bob Mizer changed it to “Tom of Finland.” Interest in his drawings grew and grew, but it was in the 1970s that it would take on an even more robust life as Laaksonen visited and showed his work in the U.S. for the first time. The “Tom of Finland” look — boots, leather, mustaches, tight jeans — became vibrant in the gay community and eventually crossed over into the mainstream via the artists it inspired. Robert Mapplethorpe became not just a fan but a friend, and photographed the artist. Andy Warhol bought several prints. Freddie Mercury donned a Tom-esque look for Live Aid in 1985.

Jean Paul Gaultier saw Laaksonen’s work for the first time in the 1970s as well, and used it as inspiration in his collections beginning in 1983, the sailor looks in particular. “I was attracted to the fact that they were covered,” Gaultier said earlier this year. “It shows the fetishism of fabric, of leather, and there were different types … in reality I think he loved clothes.” Gaultier goes on to say that Tom of Finland was, to him, a stylist of sorts: Laaksonen’s drawings, tilting the hat just the right way, inspired the designer to do the same on the runway with models. “For me, it’s more than fashion, it’s a way of life.”

Gaultier is not the only designer with whom Laaksonen’s work resonated. In the ’90s, there was even a Tom of Finland clothing line that showed at New York Fashion Week. These days, the Tom of Finland Foundation regularly collaborates with designers to create unique Tom of Finland pieces. Pierre Davis of No Sesso featured the illustrator’s images of black men on a denim jacket last year, and JW Anderson just released a capsule collection featuring a tote bag, visor and keychain this month. Swedish underwear brand CLDP released a collaboration in 2018.

“I like it when I see creatives taking his work and reexpressing it in their own way,” Durk Dehner, Laaksonen’s longtime collaborator, says. “In some ways I hold that Tom is a golden boy: he never goes out of fashion and he always continues to be an inspiration for creative people.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.