The way I remember it defies space and time.

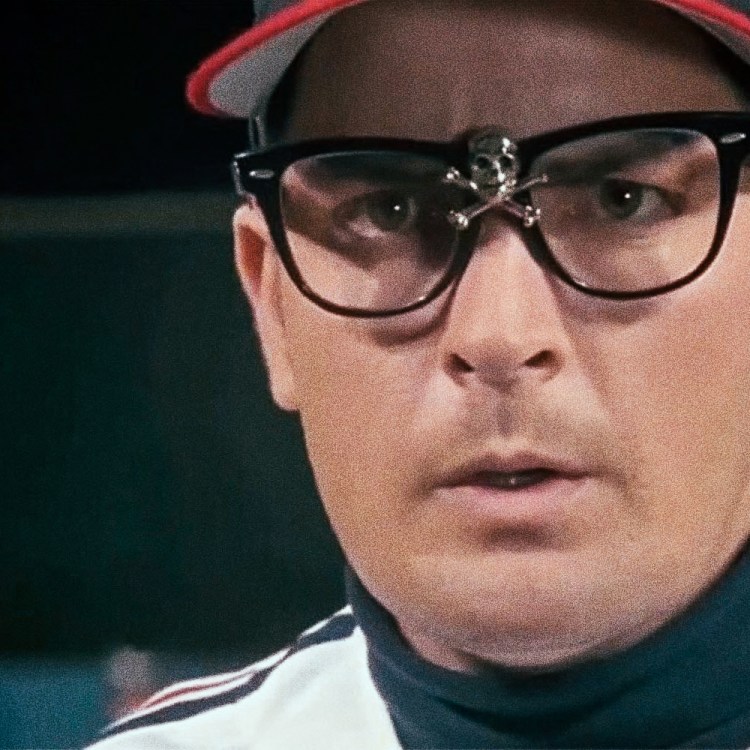

I was 10 years old but already a diehard Cubs fan when Sammy Sosa hit his 61st and 62nd home runs on Sept. 13, 1998, watching at home on TV while my dad was at Wrigley Field, working as a member of the Dixieland band that plays between innings at the park. Traffic leaving Wrigley after a game under normal circumstances is insane, so I’m sure he had to navigate his way out of a nasty bottleneck to get home, but for some reason, the way I remember it is Sammy hitting 62 and my dad immediately walking through our front door with two Cubs hats he’d impulse-bought on the way, one for me and one for my brother. It all bleeds together the way childhood memories do, cutting out anything extraneous and leaving me with the highlight reel: Sosa breaks Roger Maris’s single-season home run record, and all of a sudden my dad is handing me a Sharpie and telling me to write “This hat was given to me on 9/13/98, the day Sammy Sosa hit his 61st and 62nd home runs” on the inside of the bill. (“Given” is misspelled as “givin” because I was 10 and still all worked up from what I had just witnessed.)

As a kid, the whole thing felt like magic, but even my dad’s recollections of that day defy the laws of physics. He swears that standing behind the plate in the box seats — where, by pure dumb luck, he and the band happened to be positioned at the moment Sosa hit 62 — he could see the stitching on the ball as that fateful pitch made its way towards the bat. And then suddenly, it was gone. The noise from the crowd was so loud that his banjo started playing itself, the incredible roar causing the strings to vibrate. Everything about that day, the way we remember it at least, felt supernatural.

Of course, we all know now that that day was just one of many in Sosa’s career that felt humanly impossible because they were. He didn’t have superpowers — he just had a locker full of performance-enhancing drugs. Finding out that Sosa was allegedly juicing was not unlike finding out Santa Claus isn’t real.

It’s plain as day now that steroids were rampant in the league during Sosa’s era, and yet he remains a pariah while others who have admitted to using PEDs have been forgiven or welcomed back into the game. Mark McGwire returned to the league as a hitting coach and a bench coach from 2010-2018, and he was inducted into the Cardinals Hall of Fame in 2017. The Giants retired Barry Bonds’s number in 2018. Alex Rodriguez has been a member of ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball team since 2018. Ryan Braun was greeted with a standing ovation from Brewers fans when he returned from his 65-game PED suspension in 2014, and he remains a face of the franchise to this day.

Sosa, on the other hand, has essentially been disowned by the Cubs, banned from the team’s games and events for nearly 15 years now. Owner Tom Ricketts has said that the only way that ban will be lifted is if Sosa “puts everything on the table,” admits to his steroid use and apologizes. Sosa’s refusal to own up to his mistakes is no doubt a huge part of why he hasn’t been absolved the same way others have — it’s hard to forgive someone when they won’t admit to doing anything wrong — but his fraught relationship with the Cubs extends beyond his steroid use. His final years with the team were soured by a 2003 corked bat incident, a 2004 slump and a 30-game stint on the DL that stemmed from sneezing too hard, and perhaps worst of all, the decision to walk out on his team, with Sosa famously requesting to sit out the last game of the season that year and leaving Wrigley Field during the early innings, prompting his teammates to smash his boombox with a bat. As Long Gone Summer director AJ Schnack recently told InsideHook, “Sammy had a hard break from the Cubs. It was not a beautiful parting.”

All those factors (plus, arguably, some racial ones — Sosa has admitted to using a bleaching cream to whiten his skin tone) certainly contribute to his complicated legacy. Was he a difficult teammate? Absolutely. Did he cheat? Yes. But does that change the fact that he was one of the best players in Cubs history?

He holds the franchise’s single-season records for home runs, extra base hits, total bases and slugging percentage, as well as the team’s career home run record. Before he bulked up, he stole 30-plus bases and hit 30-plus home runs in 1993 and 1995, making him the only player in Cubs history to have a 30-30 season. He’s the only player in MLB history to hit 60 or more homers in a season three times, one of just six players with 600 or more career home runs, and one of seven players (five of whom played prior to World War II) to have multiple seasons with 400 total bases. Of course, the stats are all inauthentic now, as Bob Costas puts it in Long Gone Summer, tainted by his presumed steroid use. On top of that, his refusal to admit anything makes it impossible to pinpoint when he was clean and when he allegedly started juicing.

To be clear, he doesn’t belong in the Hall of Fame (and neither does anyone else who used steroids). But it seems silly at this point for the Cubs to discount the joy Sosa brought to Chicago’s fans over the course of his 13 seasons on the team. (It’s also worth noting that plenty of those seasons were real stinkers, with Sosa serving as the lone bright spot.) Retiring his number doesn’t seem completely unreasonable, and at the very least there’s certainly no harm in inviting him back to Wrigley Field to wave and throw out a first pitch.

Could it happen? The team recently took a break from pretending Sosa never existed by tweeting out a highlight video of him ahead of Long Gone Summer’s premiere, and Slammin’ Sammy seems convinced he’ll be welcomed back eventually, telling ESPN, “I’m expecting in the near future, they would bring me back to Chicago. Especially for all the fans who would love for me come back.” Stranger things have happened — banjos play themselves, dads teleport home from games bearing gifts, our minds play tricks on us. We know now the magic wasn’t real, but it sure made for a hell of a show.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.