Lisa Lucas first learned about the club a number of years ago during a visit to Minneapolis. While staying there with a friend there, Lucas noticed her pantry was full of glass jars filled with intricately mottled and whorled dried beans. “I was like, why do you have all these beans?” Lucas recalls asking. “She made something delicious from the mystery jars of beautiful beans,” Lucas says, and her friend told her about Rancho Gordo, the Napa, California-based company that sells heirloom legumes in part through what was then a small subscription service: for $160 a year, bean club members like Lucas’ friend receive a delivery of six one-pound bags of beans (plus one bonus item) every four months.

The meal was delicious, and the club element drew in Lucas, who is the executive director of the National Book Foundation, so she signed up. She wanted to know, she says, “Why are all these people interested in dried beans?”

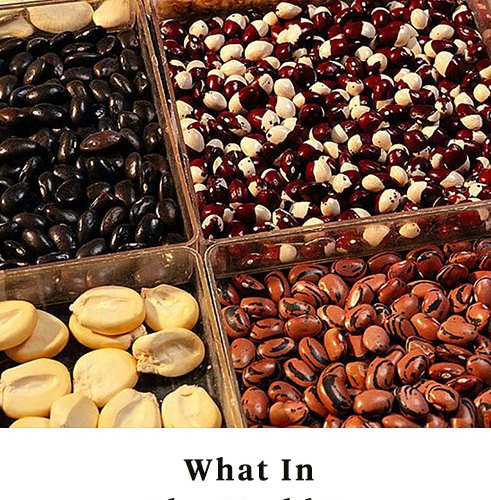

Affordable, shelf-stable, full of protein and fiber and grown on plants that have the ability to pull nitrogen (a key element of soil fertility) out of the air and fix it in the earth, beans and other legumes like lentils and peas posses an almost unrivaled utility that has made them a staple in various cuisines going back millennia. With the craze for bean club — which now has 8,500 members and a waiting list 5,000-people long — the long-time staple is now taking a star turn. For a certain taste-making set, including Lucas and the likes of cookbook writer Alison Roman, Rancho Gordo beans in particular have become both a cult ingredient and the latest symbol of “virtuous consumption,” as Rachel Monroe dubbed natural wine in The New Yorker last year. Being in bean club telegraphs that you are up on food trends and care about the fate of the planet. Owner Steve Sando says his interest in beans is primarily driven by taste — but even so, there couldn’t be a better time in world history for beans to be seen as legitimately cool.

Sando sells beans retail, but bean club has become both the heart of the business and one of the keys to Rancho Gordo’s success. Whether there’s a small amount of a new, obscure bean to try, or if one of his farmers ends up with a bad harvest, Sando has an easy answer: send the beans to bean club. It’s both a dedicated and devoted market (amounting to about a quarter of overall sales), and the one that he takes care of first. “You want I make sure the bean club people are happy, because they’re the people who tell their friends, they’re the most active on social media, and they’re the most fun because they’re so into it,” Sando says.

“People out of bean club get pissed off year after year,” he says, because they want Good Mother Stallard beans — a bean that you’d be hard-pressed to find outside of a home garden when Rancho Gordo started out in 2001, never mind for sale in a retail setting. “This is the best problem that I could ask for, but it is a problem.”

Nineteen years ago, when Sando started selling heirloom dry beans at farmers markets in Northern California, it was more a question of selling enough, not who got the good stuff. In the beginning, he was lucky to make fifteen bucks in a day. But Sando was convinced that beans were a disappearing piece of America’s cultural and culinary identity, as well as being part of the heritage shared across the Americas, so he kept at it. Growth was a steady 15 percent year over year, as Rancho Gordo went from the farmers market to the plate at Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry, and Sando started a club as a sort of joke-y alternative to all of the subscriber-based wine clubs found across the Napa Valley. By 2017, when Sando was profiled in The New Yorker, the club had 3,000 members.

After the story came out, “we got people who had never cooked beans before,” Sando says, “and I was like, why are you in the bean club?” But then something unexpected happened: a lot of those people stayed in bean club, learning not just how to cook beans, but to attend to the particularities of thin-skinned Marcellas and hearty, massive Royal Coronas. Last year, Rancho Gordo’s business jumped by 30 percent; when Sando expanded the bean club roles from 5,000 to 8,500 members last spring, he expected it would take months for it to fill up. Instead, it was fully subscribed in a matter of days.

Rancho Gordo may be the only company actively inducing bean FOMO in the world, but it’s not the only heirloom legume retailer around, and it’s not the only that’s seeing sales rise either. Glenn Roberts has followed a similar track to Sando in his work at Anson Mills, where he has worked to revive the south’s historic rice, corn, and field pea varieties over the past twenty years. While interest has been growing since he founded the company, “the last half decade has been crazy,” Roberts says. “We’re having trouble keeping up.”

Like Rancho Gordo beans, the sea island field peas Anson Mills sells are delicious, but part of what makes legumes so compelling is that the consumable product is only part of the equation. “It’s all about specificity and uniqueness,” in both pea and bean culture, Roberts says, “and there’s a vertical market in all of this.” The nitrogen-fixing peas make growing Anson’s Carolina gold rice possible, just as beans are integral to corn production even on the industrial scale, where corn and soybeans are still grown in rotation. (Rancho Gordo’s growers rotate their crops, but the beans aren’t grown in a system like Roberts’ rice farmers use.) And in South Carolina, where sea-level rise is increasing both the salinity and water intrusion on farmland, it’s the old varieties of peas that are tolerant to both salt and flooding that can help bail out farmers dealing with the harsh realities of the anthropocene. Heirloom beans — particularly the tepary beans native to the American Southwest and northern Mexico — are receiving similarly increased attention for traits like drought tolerance.

Sando understands and appreciates all of this, not to mention all of the health benefits that comes from eating beans. But the way he relates to beans is taste first and foremost. “At the end of the day if they didn’t taste great we wouldn’t be talking about them,” Sando says.

For Lisa Lucas, bean club has been a way to get back into cooking, as well as a means of changing how she cooks. “I’ve been trying to reduce the amount of meat that I’m eating, and bean club helps a lot,” she says. Lucas still eats meat, but will use it to flavor beans instead of making it the center of the meal. And unlike the CSA she used to get only to have half of it rot in the fridge, the beans can be cooked whenever, and dishes made with them take to freezing well.

There’s a bean club Facebook group for where members share recipes or talk about what came in the latest delivery, which Lucas calls “the place of least friction on the entire internet.” Instead of the chaos that now defines most social media, the page is a bunch of smart, interesting people posting pictures of things they made with their beans. “It’s deeply, deeply satisfying in a very embarrassing way,” she says.

“You don’t want to say, ‘This consumer bean subscription makes me feel like I’m part of a community,’” Lucas says. But it kind of does.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.