“It must have been taken out of circulation,” the librarian tells me.

I am agape.

It is a copy of Merrill Markoe’s 2011 essay collection Cool, Calm, and Contentious, and it is not, despite looking under two different call numbers and trying to avoid the homeless gentleman trailing me as I peruse the essays section, available at this library in New York City.

Taken out of circulation? How was this possible? As Marc Maron said on his podcast WTF in 2011, she’s “Merrill Fuckin’ Markoe”: a three-time Emmy co-winner, Daytime Emmy co-winner and six-time Emmy co-nominee; a Writer’s Guild Award co-winner; author of eight books including a New York Times bestseller; writer for classic television shows like Late Night with David Letterman, Newhart, Sex and the City, The Garry Shandling Show and countless others; star of solo HBO specials; an actor and television personality; a writer for The New York Times, The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, Esquire, Glamour and more. And on February 1, she will be awarded the Writers Guild of America West’s 2020 “Paddy Chayefsky Laurel Award for Television Writing Achievement,” which is given to a Writer’s Guild member who has “advanced the literature of television and made outstanding contributions to the profession of the television writer.”

And the librarian cannot spell her name. “M-E-R-Y-L?” she asks me.

“No,” I say, still dumbfounded. “M-E-R-R-I-L-L.”

Weirdly, though Markoe will soon receive an award that has also gone to the likes of household names like Aaron Sorkin, Shonda Rhimes and Larry David, this is an interaction I will find myself having often when I discuss Markoe with people outside the comedy world. “I am deeply honored and grateful and quite frankly a little shocked that the Writers’ Guild actually knows who I am,” Markoe writes to InsideHook via email. The consummate writer, Markoe prefers to craft her answers to questions via email. Here, I cannot tell if she’s joking. I’m not sure if it matters.

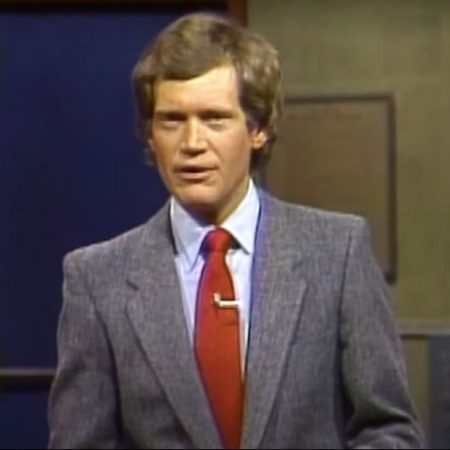

Don’t get me wrong, inside the comedy world Markoe is a legend, an icon, a master whose successful career of over four decades has rarely been duplicated. But outside of comedy, I learn, not nearly enough people know who she is. Instead, they are far more familiar with the man whose career she helped launch some 40 years ago, on whose show she pioneered now-standard late-night comedy practices and thereby changed the face of modern comedy, a man initially reluctant to many of her absurdist, out-of-the box ideas for which his show later became known and influenced a generation of comedians who followed him: David Letterman.

Markoe met Letterman in the mid-1970s when she was doing standup at The Comedy Store in Los Angeles and writing for shows like the second iteration of Laugh-In (which featured a young Robin Williams). She and Letterman were in a relationship for 10 years. She spent part of that decade as head writer first for The David Letterman Show, a daytime talk show, and then Late Night with David Letterman, ultimately stepping down from the latter to be just a staff writer in hopes of preserving their relationship, which had become difficult when blended with work. They broke up in 1988, and Markoe left the staff.

But prior to Letterman, Markoe had developed a career on her own as a successful comedy writer, which she also resumed after the show, to the point that merely listing her as “David Letterman’s ex-girlfriend,” as many publications have in the past, is insulting. Rather, Letterman should arguably feel quite lucky that he was Merrill Markoe’s ex-boyfriend. Her contributions to Late Night with David Letterman included not just the unorthodox sense of humor for which the host and the show would ultimately become known, but the self-aware “Stupid Pet Tricks,” “Viewer Mail” and the remote segments in which people on the street became part of the show’s comedy. She has also cited the show’s “We Are the World”-like anthem “Late Night World of Love” and “Dog Poetry” as favorite bits. What they all have in common is their status as pieces of showbiz meta-commentary, at once skeptical of and complicit in the entertainment machine that begot them.

“You see all these people on YouTube do something funny or The Daily Show going out in the street doing things with ordinary people or Sacha Baron Cohen doing stuff in the real world,” Jason Zinoman, author of the 2017 book Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night, tells InsideHook. “That was not a big thing before Merrill Markoe came along. She’s the one who pioneered all those remote [segments], this comedy on the street. Billy Eichner [reveres] Letterman, but he really reveres what Merrill Markoe created.”

And Billy Eichner is, of course, not the only one. Veteran comedy producer Mike Royce, who worked on Everybody Loves Raymond and the newly reimagined One Day at a Time, only realized Markoe’s contributions after reading Zinoman’s book. A longtime Letterman devotee, he was so moved to learn about Markoe’s impact he wrote about it on Medium. “David Letterman was my everything. What I didn’t realize at the time was that Merrill Markoe was also my everything,” he writes. “She was at the center of the Letterman comedy ethos that shaped and inspired a generation of comics and writers, including me.”

When Markoe worked on both incarnations of Letterman, Zinoman says, auteurship was the name of the game. That is, late-night talk shows heralded the host first, whether or not they actually impacted the show’s writing. Writers were mostly secondary and were not the names they are today, when we know John Mulaney and Julio Torres from Saturday Night Live, Dan Harmon from Community and Rick and Morty. Not to mention the number of women in writers’ rooms was even lower than it is now. As Royce wrote, “There are still a lot of people out there who think ‘women aren’t funny.’ In 1980 there were a lot more.”

After her relationship with Letterman ended but before the show became the cultural juggernaut it would be just a few years later, Markoe left. To this day, she doesn’t get recognized for her contributions to the show as often as she should. “For all those people who love Letterman because he was different than Johnny Carson, and was doing all this innovative, weird stuff, which is a huge number of people, Merrill deserves the lion’s share of that credit,” Zinoman says.

Markoe wrote for television on and off after Letterman, also finding a vibrant career in humor writing. “At some point, I became ill at ease with the idea that no one knew what my contribution was,” she said. “I was looking for evidence of my own ability. It was the same thing that drove me to stand-up comedy.”

When offers to write for print arrived, she took the opportunity, finding it energizing to hear her own voice in writing. She had modeled much of her own humor after the witty, urbane, dry and cerebral Robert Benchley, a former New Yorker editor and part of the Algonquin Round Table. “I read his stuff over and over and over, trying to make sure it was imprinted on my DNA,” she said. She also mentions humorist S.J. Perelman as an influence, as well as Dorothy Parker and later, Nora Ephron. She found the latter particularly revelatory, how Ephron showed her “you could work with your own deficits and reformat them as assets,” she tells InsideHook. “There is no awkward experience or nerve-wracking one that I live [through] in the world that does not immediately begin to reshape itself into a story I can use either on stage or in some format.”

In the 1980s, Markoe was offered a column for a small print magazine called N.Y. Woman alongside famed playwright Wendy Wasserstein. The column became so successful a publisher offered to collect the columns into a book for publication. “And voila: I was an author,” Markoe says. “I started to believe that it might be a smart career tactic for me to go through the doors that opened, since I was finding it frustrating to just sit and wait for a pilot I wrote or a script to get picked up or made.”

She decided to make herself available to any writing opportunities that crossed her path, as long as they allowed her to be creative in the right way, she says. This included a role as a comedic on-air camera reporter for Los Angeles’s Channel 13 News at 10 in a bi-weekly segment called “Merrill’s L.A,” as well as a number of her own HBO specials, including “Merrill Markoe’s Guide to Glamorous Living,” which she has since put on YouTube in full. She has also written both novels and essay collections, a recent audiobook called The Indignities of Being a Woman with comedian Megan Koester, and is currently tapping into her former life as an art professor while she works on a new graphic novel. “She has a wide, incredibly well-rounded wide range of interests as an artist, as a comedian, as a writer and she keeps growing and evolving with the times and getting hired,” Zinoman says. “This is not common.”

Markoe found a way to free herself from the anonymity and the negativity of her past. “The liberating part was realizing that I could demonstrate ability without a middle man or a collaborative team. That was kind of a relief. Because a lot of my collaborators over the years have been brilliantly funny and creative. My upbringing was such that it is my instinct to think that even though I worked hard, bottom line is that I contributed nothing of value. That was the lesson my mother taught me, and therapy taught me to fight against it every day,” she says.

“The challenge is that, although you get the credit for your work, you also get the blame if it’s weak or lame. But that’s the core of being an artist and why most people go into the arts to begin with … in order to do the work, and then accept the blame or get the credit. It’s a way to stand out and get a little attention. Most artists are, to varying degrees, starving for attention. The ones who are hungriest are frequently the most successful.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.