Last March, my husband and I moved to a larger apartment, a modest upgrade that nonetheless forced us to confront a brazen shortage of furniture: namely, bookshelves. While unpacking, we realized that we require many, many more of them in order to accommodate our library, which has steadily grown to absurd proportions. Now, finally, we can add new bookshelves to our repertoire, and unsurprisingly, I’ve become engrossed by my search for them. After all, no living space feels intimate when one’s books are packed away. If I haven’t organized my stock of Victorian novels, I’m just visiting.

There is a unique pleasure in organizing a bookshelf, one that unites intellectual interests, material indulgence, and the fashioning of an idealized self. It’s an aesthetic exercise that broadcasts, simultaneously, the sort of person we think are and who we aspire to be. But despite the fun of curation, it can also be preoccupying: as soon as I load up a bookshelf I inevitably second-guess my choices.

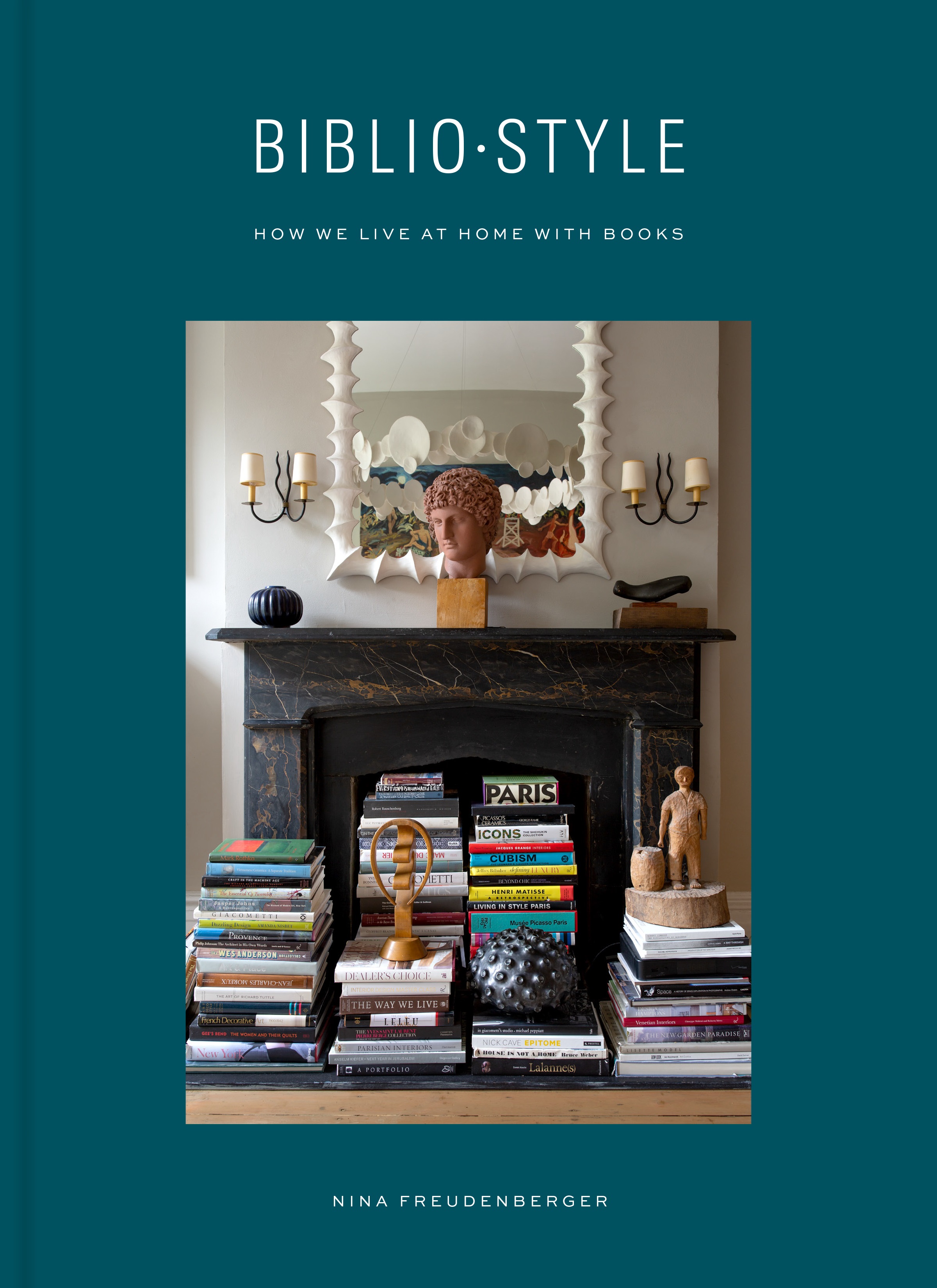

Recently, InsideHook spoke with Nina Freudenberger, an interior designer and author of Bibliostyle: How We Live With Books in an effort to better understand both the specific appeal of a lovingly schematized bookshelf and how a hapless person like myself might put one together. Bibliostyle took Freudenberger on a global investigation, and over its course, she, together with co-writer Sadie Stein and photographer Shade Degges, interviewed subjects whose lives are both imbued and structured by their love of books. Illustrator and author Joana Avillez sleeps in a Murphy bed tucked into a wall of bookshelves, devising for herself a literary canopy. Writers Darryl Pinckney and James Fenton are restoring a nineteenth-century Harlem townhouse, where, in addition to their respective studies, they have allocated four separate rooms as libraries. The methodologies and aesthetics featured in Bibliostyle are myriad, but what prevails is a unifying tender responsibility toward books — a determination to carve out space for them, live in their midst, and honor them as precious artifacts of both personal and public history.

“My first book, Surf Shack, was about people building homes around something they love doing, which was surfing,” Freudenberger says over the phone. “And I was so inspired by that, and a commitment to a lifestyle and a passion that I wanted to keep exploring…‘[What] thing do [people] love so much and feel so strongly about…that [they] build homes around?’…I came down to books.”

Freudenberger sought out book collectors with diverse inclinations, in art and in home building. Accordingly, she encountered numerous spaces where books coexist with their readers in less regimented ways. They blossom from the floor in colorful piles, sidle against hallway tables, and sun themselves on desks. Even a (dormant) fireplace can serve as handy, visible storage. So, it is no surprise that when I confided to Freudenberger my present bookshelf deficit, she told me not to sweat it.

“Don’t spend more on your bookshelves than you do on your books,” she advises, pointing out that books will always, eventually, settle into one’s living quarters. Her philosophy on organizing a bookshelf is similarly mellow and refreshingly practical. She emphasizes “accessibility” and “functionality, first and foremost.”

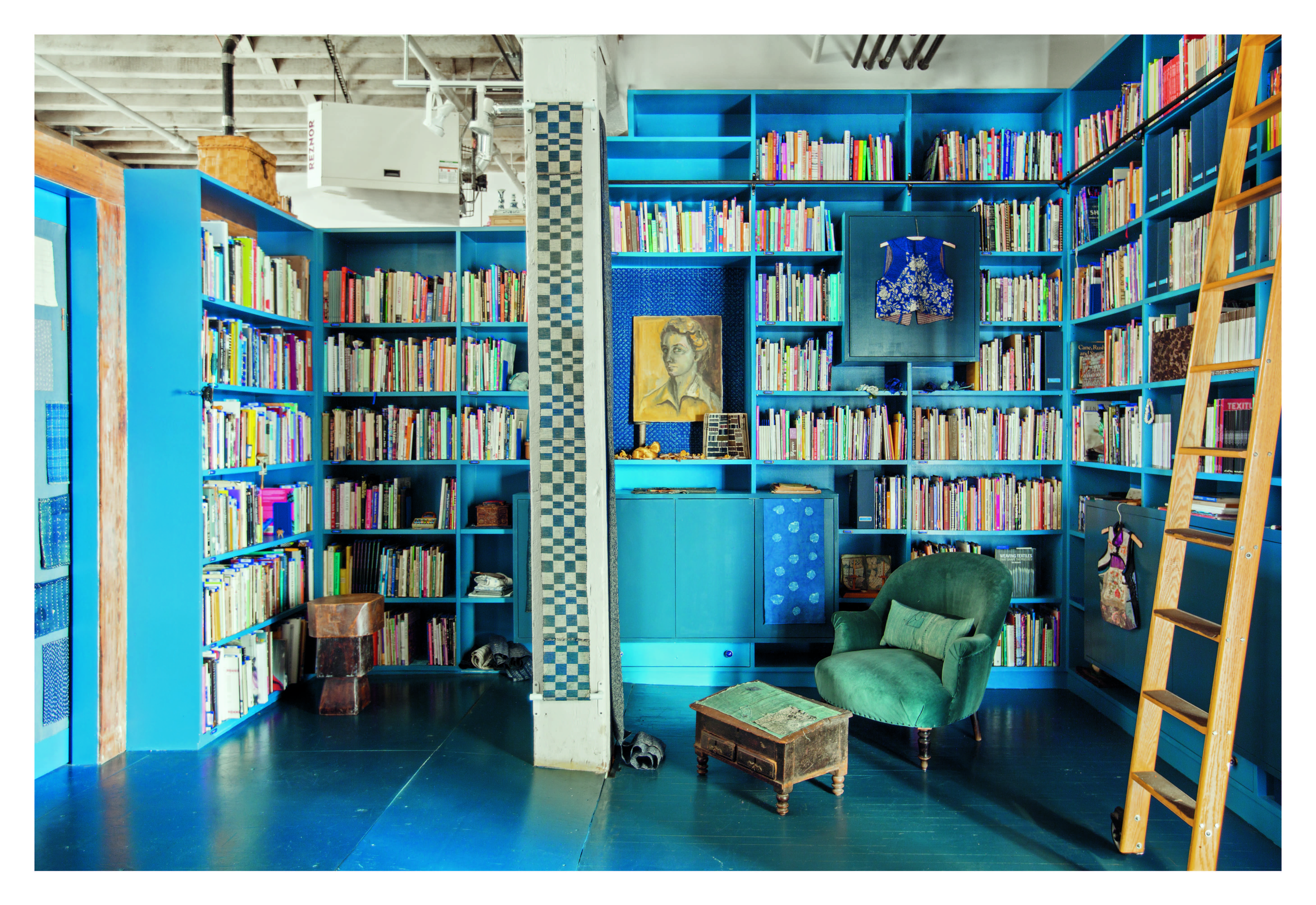

“If [your books are] going all the way to the ceiling, make sure there’s a way to get to those books at the ceiling,” Freudenberger cautions. Although she specifies that Bibliostyle’s focus is “the actual, physical love of books” — a passion distinct from “the act of loving stories or reading”— the two are, ideally, intertwined. An extravagant, Disney-esque library that would give Belle from Beauty and the Beast an orgasm feels remarkably like a mausoleum if the books merely serve as decoration. (I recently came across photos of books tacked fancifully onto walls with, in some cases, stray pages cut out. Reader, I nearly had a stroke.)

Freudenberger regards these ornamental book arrangements — see also: books wrapped in the same color, or with spines facing inward — as “inauthentic.” Nor is she compelled by the trend of color-coordinated bookshelves.

“The people that are color-coding by spine color are really looking at these books exclusively as [objects] at that point…It’s a color wrapped object.” She mentioned, however, that when she once critiqued this aesthetic on Instagram, some took umbrage.

“I was totally blown away, but I actually got quite a few emails [from] people that were very, very upset…[S]omeone said, ‘I feel like you were judging me. I actually love my books. And since the age of two or four or whatever, I’ve been color-coding my books; that’s how I organize [them].’ And I felt like, ‘Well, then fine…That’s authentic to you…[T]hat’s your system that you genuinely use.” Still, Freudenberger cannot fathom an arrangement in which the books themselves are subordinate to a larger, decorative contrivance.

“It becomes removed from the human touch,” she observes. “It doesn’t feel like a working library…All the libraries I [featured in my book] were…working libraries.”

Freudenberger’s interest in “working libraries” — book collections that are always in motion — shapes her deliberate, yet unfussy curation method.

“I think that books are so beautiful when you buy them one-by-one…I love a slow process,” she says. “If you’re just buying [books] to fill a bookshelf, then it’s gonna get really expensive and not feel good.”

More meaningful is a library born from a series of emotional impulses — ones rooted by temporal and experiential precision.

“I love collecting books when I travel,” Freudenberger says. “It’s super inconvenient, but I freaking love it, coming home with the…books I chose [while I was away.] ‘Cause you often can’t find them when you come back…You have to buy them on the spot.” And while she notes that first editions “are lovely to have,” she doesn’t consider them necessary to a vibrant library.

I fantasize about the sort of wealth that would enable me to buy a first edition copy of Middlemarch. But books are always a luxury, and most of us must make choices. Like Freudenberger, I revisit memories through my books, so, when I travel, I look for used bookstores, where I’m most likely to discover peculiar editions of old favorites. I rely on paperbacks for titles I will frequently reread and mark up, but I’m also likely to purchase antique copies of the ones dearest to me (often, you can find early twentieth-century hardbacks for ten or twenty bucks). Sure, they look lovely on a shelf, and are not so predictable as a Norton critical edition or Oxford World Classic, but I am largely motivated by emotional attachment. I seek something beautiful that seems to reflect my admiration for it.

Coralie Bickford-Smith’s covers for Penguin’s Clothbound Classics pay homage to long-beloved authors in this way (Bickford-Smith is another individual Freudenberger interviewed for Bibliostyle). Inspired by William Morris’s Pre-Raphaelite Arts and Crafts Movement, her designs are compellingly metaphorical and minimalist: Bram Stoker’s Dracula, for instance, is wrapped in garlands of garlic flowers, while Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is embossed with the repeated illustration of a human heart. Independently owned shops, particularly ones with a specific focus or mission, like the London-based Persephone Books (featured in Bibliostyle), Loyalty Books, located in Washington, D.C. and Silver Spring, and of course, New York City’s The Strand typically offer more distinctive wares.

But rarely are books bought so that they can hibernate in a storage room; upon acquisition we must figure out what to do with them. As Freudenberger remarks, “It’s the ultimate puzzle…[W]e find so much joy in books, and then we…grapple with how to deal with them as…object[s].” There are, however, certain completist tendencies to which I adhere and which follow a logic of sorts. A series, like Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet, should always be shelved together. It does not make sense to separate Toni Morrison’s novels from her nonfiction unless you are determined to organize by genre.

Above all, decide on a system that feels intuitive. I rely on chronology, and then alphabetize within broad literary periods, like Romanticism and Modernism — but I am also an incurable, Type A dork. One of Freudenberger’s subjects employs a version of the Dewey Decimal System, but a complicated and erudite method like this is only as valuable as it is useful. What’s more, curating a bookcase will probably always involve a degree of showboating: if you want to place your vintage Ray Bradbury paperbacks or first edition of Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle at eye level to impress those attending your literary salon, go for it. That said, flourishes should never impede the larger objective: to locate your books when you want them.

Or, dispense with bookshelves altogether. This was Freudenberger’s concluding advice, and I’m still mulling it over.

“Don’t even buy bookshelves,” she says, gently blowing my mind. “You can stack them, use them as a coffee table…Just put the books out and then they will start to float around, find a home.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.