In the beef business, there’s probably no variety of steak that gets more sizzle within the industry than Kobe cuts obtained from Japanese Wagyu cattle.

Though it doesn’t get as much hype as its Japanese cousin, there’s another brand of high-quality beef you should be chewing the fat with your butcher about: American Wagyu.

Unlike Kobe beef which is made from 100 percent Wagyu cattle raised in the Kobe prefecture of Japan, American Wagyu consists of USDA-approved beef taken from cattle that are 50 percent Wagyu and 50 percent Angus or another high-quality domestic breed.

Don’t let that mixed pedigree fool you as Dave Yasuda of ranch-to-table meat purveyor Snake River Farms says American Wagyu is used to produce a “best of both worlds” steak.

“American Wagyu has the richness and marbling of Japanese Wagyu beef and the flavor of high-quality beef that Americans prefer,” Yasuda tells InsideHook. “People understand the delicious difference of American Wagyu beef as soon as they take their first bite.”

According to Yasuda, American Wagyu — which is more expensive than USDA Prime meat but is significantly cheaper than 100 percent Wagyu — stands out in three key areas: taste, texture and juiciness.

“American Wagyu is highly regarded for its rich beef flavor,” Yasuda says. “This is due to the large amount of fine marbling that is distributed throughout each steak. The marbling, or fat, melts at a lower temperature than conventional beef and produces a buttery cut of beef. American Wagyu takes longer to raise and requires more specialized feeding to create this higher level of marbling.”

As for the texture, American has “a slightly firmer bite and superior mouthfeel,” Yasuda says. But, despite the firmer bite, the beef is tender and should easily yield to a dull knife. And the juiciness? “The abundant marbling melts to produce a more juicy and unctuous steak,” Yasuda says.

“Japanese Wagyu is very high in fat and has a really rich mouthfeel. There’s a sweetness, kind of a subtle, beefy flavor. It’s very rich.” Yasuda says. “USDA Prime — that’s a robust beef steak. It’s going to be beautifully marbled, it’s going to have a juicy characteristic because of all the fat. It’s really going to be melt in your mouth. In the middle, American Wagyu combine those two characteristics. You’re going to have a higher amount of marbling. Marbling equals flavor, and it equals juiciness. When the fat melts, it’s very luscious on the palate and has a lot of flavor.”

To make sure you get to appreciate American Wagyu’s taste, texture and juiciness in all its glory, especially with a big piece of meat, Yasuda endorses using the reverse-sear technique because it eliminates some of the guesswork that comes with other cooking methods. “Instead of searing and cooking, you get it to temperature and just sear it to finish,” Yasuda says.

To start, you’ll want to put a wire grate in a decent-sized pan and then load your steak into it — after seasoning of course.

“Season the hell out of that thing,” Yasuda says. “I’m a salt and pepper guy. I’ve also heard people talk about don’t put pepper on it because it gets bitter. Use a grainier salt. Table salt’s also fine. Just buy a box of kosher salt, it’s inexpensive.”

Once that’s done, it’s time to head for the oven.

“The idea is to slow roast it. You can do it as low as like 200 or 225 degrees, but I find that tries my patience,” Yasuda says. “Two-hundred or 275 is probably better and it doesn’t overcook it, but you’re going to let that thing slow roast, especially with a big steak. We’re going to have to get that steak’s internal temperature up to 128. For a thick steak, it’s going to probably be an hour or maybe a little less.”

For best results when checking the steak’s temperature, Yasuda suggests using a digital thermometer.

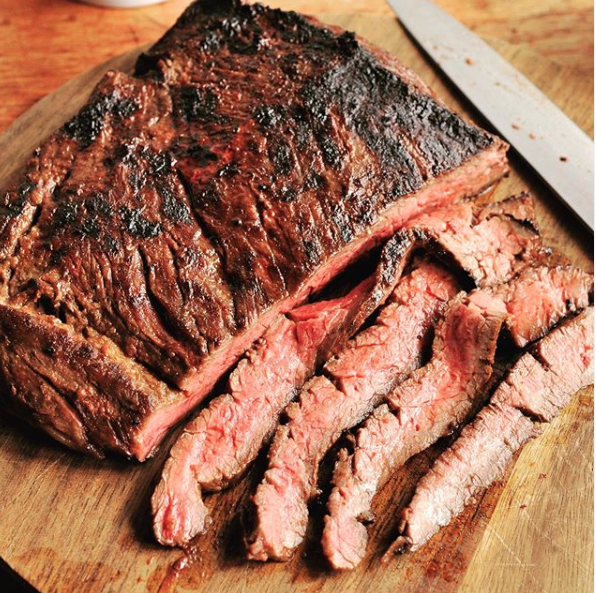

“I always start checking, no matter what, at like at half an hour, just to be sure,” Yasuda says. “Then, when it gets to the 128, degrees you pull it out. It’s kind of nice because at that point it can kind of just hang out. If I was having people coming over and they were late, I’m not going to sweat it at all. It’s not critical to let the steak rest at that stage. When it’s time to reverse it, get your carbon steel or my cast-iron pan prepped with grapeseed oil and crank things as high as they’ll go. Then, you sear it on both sides for 60-90 seconds. This time it’s nice because you don’t want to do it too much because you’ll see it start cooking inside if you leave it on there too long. After searing, it has that crust. Like when you slice that with your knife, it takes a minute to bite through and then it goes … I’m kind of salivating thinking about it.”

After cleaning up your drool, there’s just one more thing to do.

“Pull it out of the skillet, put it on your cutting board and let it rest for 10 minutes. That resting is huge,” Yasuda says. “If you cut a steak rare like that, the juice just flows out like crazy. Let it rest, and juice aside, it’s going to continue cooking. I think resting is the secret sauce, as long as it’s the right temperature. You don’t want to eat anything when it’s super hot because you don’t really taste it. Resting allows the meat to firm up and the juices to come back in. Steak is pretty simple. Don’t mess with it too much.”

Like Tom Petty — an American if there ever was one — said, the waiting is the hardest part.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.