Canadian photographer Greg Girard has earned acclaim over the years for his richly detailed photographs of cities around the world. He’s also a favorite artist of acclaimed novelist William Gibson, who wrote the foreword for Girard’s 2007 book Phantom Shanghai. Girard’s works frequently focus on subcultures, hidden structures or unexpected histories.

His latest book, Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983, finds Girard exploring the recent past of Tokyo — but also his own artistic development. Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983 includes a host of photographs taken by Girard when he was a young photographer first venturing across the Pacific and shaping his distinctive style.

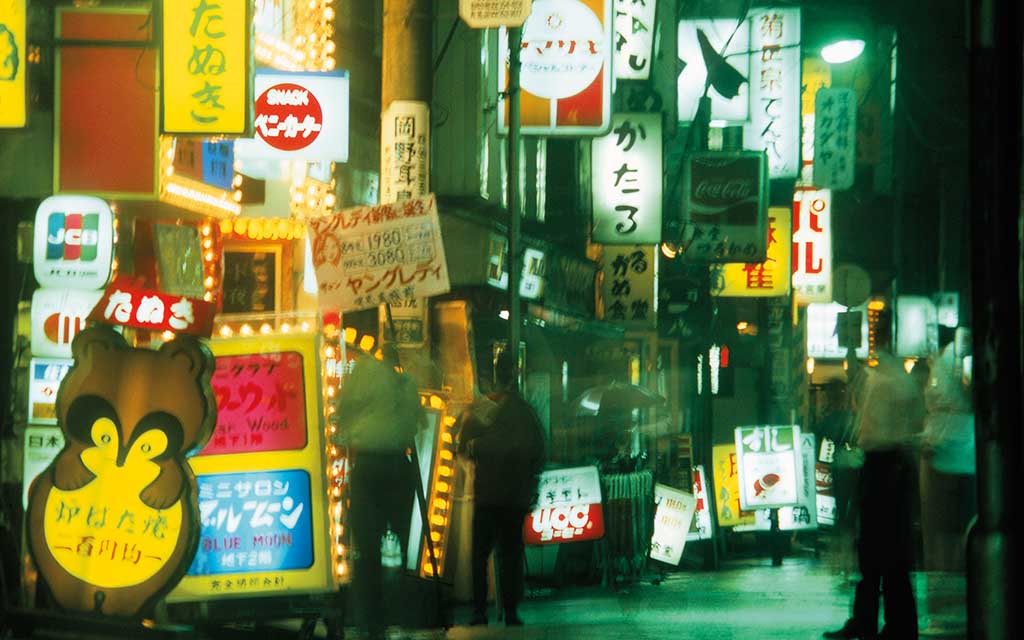

In his introduction, curator Christopher Phillips writes that “[f]ew would have described the Tokyo that Girard discovered in 1976 as one of the great destinations of the world. Foreign visitors were more likely to complain that Tokyo was a planless maze: chaotic, featureless, polluted, a city concerned only with economic growth.” It would be a few more years before Tokyo became the iconic city — and muse to designers and artists around the globe — that it is today.

Reading Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983 also offers the opportunity to see how Girard would develop some of the themes he’s explored in the years and decades since then. In 2012, Hyperallergic wrote about the International Center of Photography’s exhibit Perspectives 2012, in which Girard was one of the featured artists. The review hailed Girard’s exploration of the American military presence overseas, stating, “[w]ith his provocative series of photographs, Girard manages to question our military presence in the Pacific by simply showing that we are there.”

One can see the genesis of this work in Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983: there are glimpses of military facilities seen from a distance, providing the viewer with an empathic glimpse of those structures and the security systems around them.

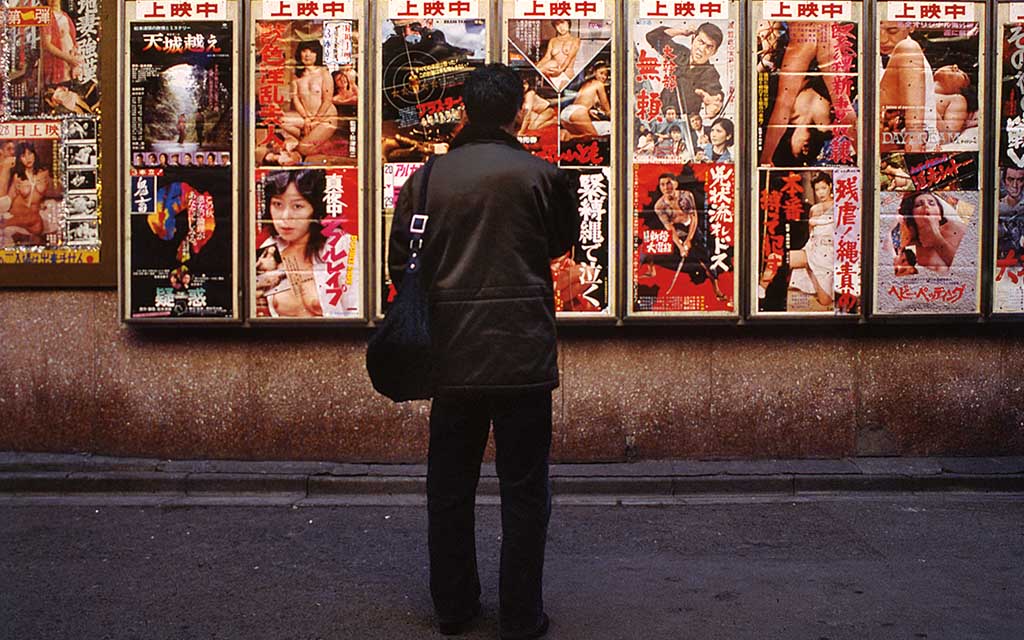

Some of the most impressive images within Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983 contain within them a sustained atmosphere, evoking the everyday atmosphere of the city and its residents going about their daily routines. In some of Girard’s images of buildings and signage, you can practically hear the hum of the glowing signs as they provide a signpost to viewers traveling through the city at night. In another, an empty playground structure is bathed in a wash of green light, turning a familiar sight into something disconcerting.

The people glimpsed in Girard’s photographs are also instantly memorable. Whether he’s capturing them in intimate moments or showing them channeling an inner levity, Girard finds unexpected moments in the lives of his subjects. Phillips’s introduction memorably cites one in particular: “At one of his regular late-night haunts, a 24-hour Mr. Donuts shop in his Tokyo neighborhood, he bends down to photograph a drunken off-duty sushi chef who is good-naturedly performing a ‘yakuza greeting.’”

The photographs seen in Tokyo-Yokosuka 1976-1983 offer a window into a great photographer’s formative years, and to an oft-overlooked period in the city that they depict. But Girard’s work never loses sight of the human element, and it’s what lends these photographs considerable power, decades after they were first taken.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.