2019 is a year full of milestones for Billy Joel, starting this week with his 70th birthday. February marked the 40th anniversary of his Album of the Year Grammy win for 52nd Street, while October will be 30 years since he released Storm Front and millions of people found themselves trying to remember all the words to “We Didn’t Start the Fire.” But you might not realize those things, because for whatever reason, Billy Joel doesn’t get the respect he deserves.

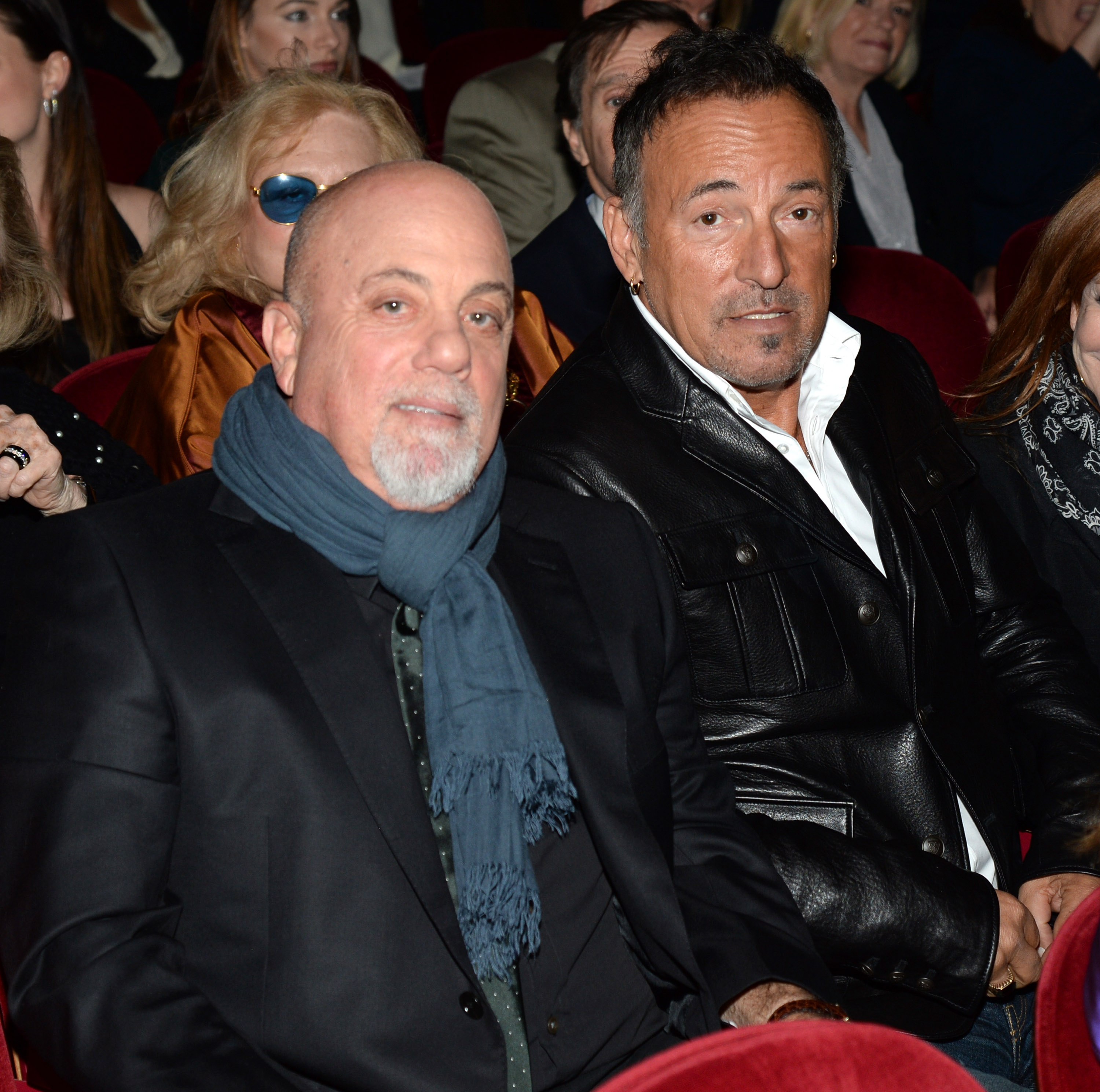

But what are those reasons? Joel, just like Bruce Springsteen, Bob Seger or so many of the other staples you might hear on the classic rock radio stations, was a journeyman. Read any bio of any musician to hit it big in the 1970s, and you’ll see their careers usually started in the ’60s or early ’70s, either writing songs for bigger stars or in some garage band who maybe had a minor regional hit, then tried and failed to reinvent themselves, until finally landing on something that stuck. Joel’s previous attempts included his time in the blue-eyed soul group The Hassles to his strange, “psychedelic bullshit” period in the band Attila that falls somewhere between hard rock and prog, and was his failed attempt at doing “what Hendrix did,” but “with a piano.”

Yet Joel, more than of all of his contemporaries, still has to deal with the most backlash to this day. Sure, when you’re rich and successful and have become tabloid fodder for your marriage (number two of four) to a supermodel, you battle publicly with depression and addiction and have had multiple car accidents, people have more than enough ammo. And yes, Joel’s music is really not for everybody. He’s not heavy, not exactly experimental; he’s a pop songwriter influenced by stuff that came out of the Brill Building, George Gershwin and Ray Charles. He might be too sentimental or even hokey in the way classic songwriters he emulated tended to be for some, and that’s understandable. Yet the vitriol directed towards Joel, like a Tablet article from 2017 entitled, “Billy Joel, the Donald Trump of Pop Music,” shows that some people are never going to quite get the Piano Man. Starting off with a James Baldwin quote before moving on to a short review of one of Joel’s Madison Square Garden shows, the writer, Liel Leibovitz, had his weapons sharpened and ready to go from the start. He call’s Joel’s music “solipsistic and soulless schlock,” and “singularly awful” in what has to register as one of the roughest pop-culture hatchet jobs of that year.

Leibovitz wasn’t the first to take aim at the singer-songwriter, and he definitely won’t be the last; it’s sort of a time-honored tradition. In 2009, writing for Slate, Ron Rosenbaum called him “The Worst Pop Singer Ever.” Robert Christgau, who gave Joel’s first three albums C grades, finally bumped him up to a B- with The Stranger, while also taking an opportunity to call Joel a “spoiled brat” and “as likable as your once-rebellious and still-tolerant uncle who has the quirk of believing that OPEC was designed to ruin his air-conditioning business.” Joel would famously respond by ripping up Christgau’s reviews during concerts. Other reviews of his albums in the 1970s were lukewarm, often complete with backhanded compliments: “While I’m not a fan of everything that Joel cranks out,” wrote Timothy White for Rolling Stone in 1981, “I love his ballsiness.”

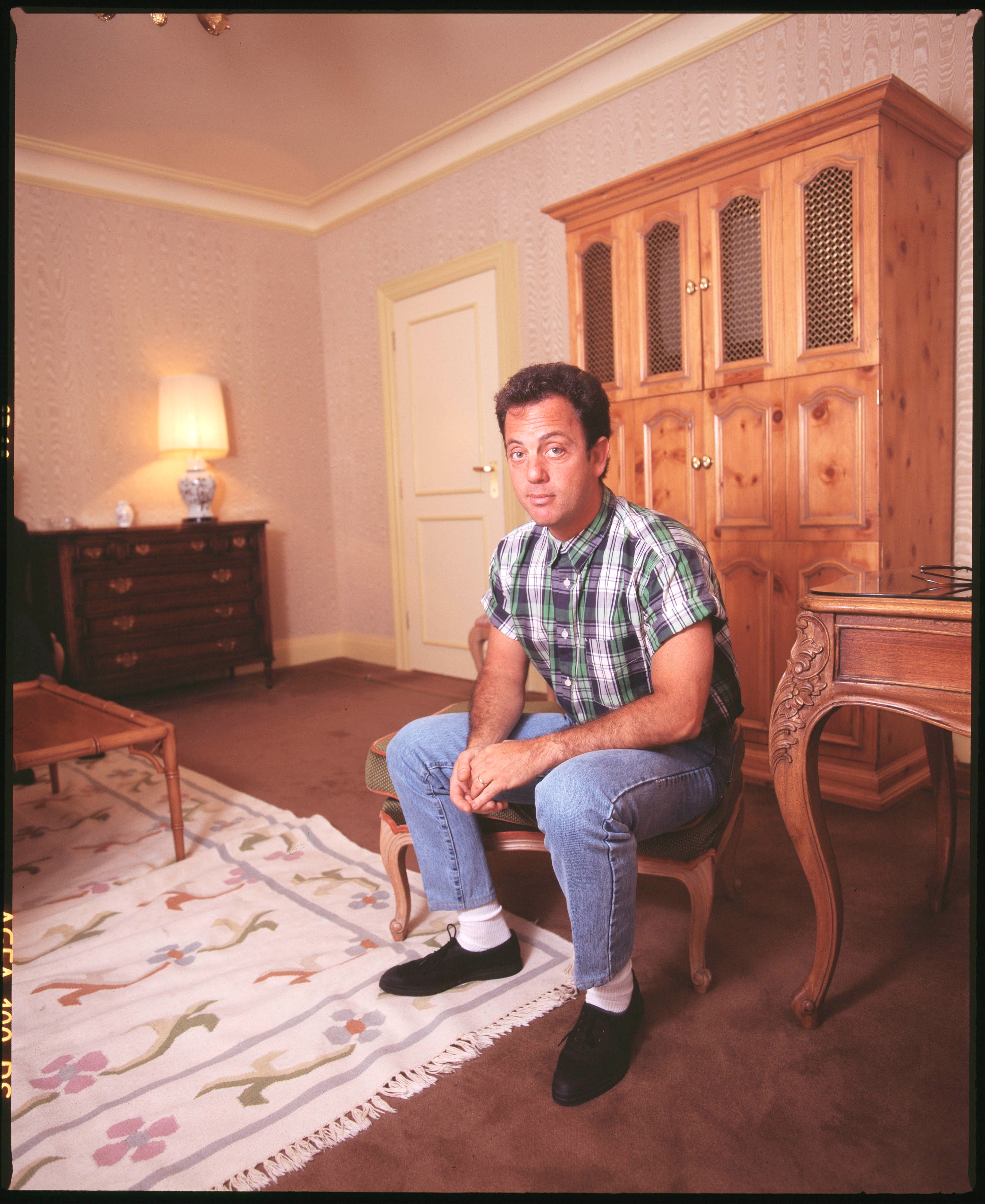

Nobody has ever wanted to fully admit to liking his music. Billy Joel was never truly in style, and that was something he relished in. He was never the sound du jour throughout a career that saw hard, soft, punk rock, new wave and hip-hop rise, and Joel never seemed to care. That’s one of his great qualities; the other is that he has written a ton of songs that will endure no matter what people want to say. Chuck Klosterman, in a 2002 profile for the New York Times wrote that Joel “never seemed cool.” Over 15 years later, I wonder if he’d revise that statement. Just look at any photo of Joel in the late-70s into the 1980s, and you’ll see his various looks, whether it’s rocking classic Nike running sneakers or the black leather jacket, are suddenly seeming less dorky. His cool-dad style, like Paul Simon or characters from Nora Ephron’s rom-coms, are trendy now.

Sure, he has enough money to take a private helicopter from his Long Island home to Madison Square Garden (and annoy his neighbors in the process), and yes maybe he plays up the hokey every now and then, but that hokiness is what the great American songbook was built on. From the Gershwin brothers and Jerome Kern to the Magnetic Fields today, there is always an element of wordplay and silliness in the greatest American songs.

Will Stegemann grew up 25 minutes away from Joel’s hometown of Hicksville. Long Island is a strange mishmash of all five New York boroughs; it’s both the butt of a thousand jokes told by people who live in the city and the place New Yorkers go to escape the heat of summer. As Stegemann points out in the Last Play at Shea live concert documentary, Joel sums up being a Long Islander as “perpetually feeling like they are close to NYC but also a million miles away from it.” Stegemann, however, counted himself among those that didn’t like Joel’s music despite the singer’s hometown hero status. For 30 years, he disliked him, but could “no longer articulate why.” So he started the “A Year of Billy Joel” project, where Stegemann spent 365 days listening to every single Billy Joel song, “in an attempt to understand his massive appeal and why I disliked him so much.” As a lifelong fan, I read along all the way to the end when Stegemann found himself at a Joel concert at the Hollywood Bowl, “happily singing along with the rest of the crowd.”

I read nearly every one of Stegemann’s posts for precisely the same reason I read nearly every single Joel hate peace that comes out every year even though Joel hasn’t put out an album of original rock songs since 1993’s River of Dreams (2003 saw the release of his first and only album full of classical compositions, Fantasies & Delusions), but unlike the few thousand words writers tend to dedicate to dismissing Joel and his entire body of work, Stegemann took an entire year to better understand an artist that I was raised on. It was a nice way of thinking, I thought: listen and try to understand instead of hating. The world could use more of that.

A little over a decade ago I found myself in a hotel on the Lower East Side interviewing Mick Jones of The Clash, and I had a moment that bridged my childhood love of Joel’s music with everything that came after.

I grew up listening to Joel. I had a picture of him on my wall when I was a kid; my dad would drop me off at my mother’s playing “The Longest Time” off 1983’s An Innocent Man (one of the few truly tender memories I have of my father growing up) and the first CD I ever purchased was Joel’s 1989 album Storm Front. Somewhere along the way, I got into punk and did that annoying teenage punk thing where I swore off anything on the radio, but I never could quite shake my love for Joel. At some point in the pre-Wikipedia era, I noticed that the producer credited on the album that gave us “We Didn’t Start the Fire” was Mick Jones. For about a decade, I operated under this idea that it was, in fact, the same Mick Jones who was part of one of the greatest songwriting teams in rock history with Joe Strummer –– only to find out at some point in my 20s it was Mick Jones from the band Foreigner.

During my conversation with him, I mentioned this tidbit to (Clash) Mick Jones in an attempt to break the ice, guessing the guy from one of the greatest punk bands ever, one of the legends in the genre that was supposed to be against everything guys like Joel stood for, would find that funny. Instead, Jones, who up until that point had been jovial and possibly a little drunk got really quiet and serious. “Billy Joel,” he looked at me, “He’s the great American songwriter.” I didn’t bother to ask if Jones was taking the piss out of me or not, but it really didn’t seem that way. I walked away satisfied, believing that Joel had the respect of a member of The Clash.

Regardless of whether Jones was kidding, he’s right: Billy Joel is one of the greatest American songwriters. His output from the ‘70s alone was enough to plant that flag. He fulfilled one of the duties to be included among the best songwriters by penning an iconic ode to a location. Robert Johnson sang about “Sweet Home Chicago,” Aaron Copland composed his Appalachian Spring, Allen Toussaint had his moving tribute to Southern nights; Billy Joel thought the city that had a thousand songs already written about it needed just one more, and delivered “New York State of Mind” from 1976’s Turnstiles. He kept inching closer and closer toward the respect he deserves; even Christgau had to admit Joel’s “craft improves” on his fourth album.

Yet it wasn’t the album, the way Born to Run had been for Springsteen a year earlier, the one that got him over the hump from popular to massive. Joel’s career was at a crossroads. He had fired producer James William Guercio and took on the task of making Turnstiles on his own. It wasn’t a bad record by any means, with a few songs that would become greatest-hits compilation staples — but it wasn’t The One.

By the summer of ‘77, Joel was enough of a name that he could play Carnegie Hall, just as everybody from Duke Ellington to The Beatles had. He opened the early June concert with the final song from his last album, which 40 years later sounds almost Nostradamus-like in its dystopian prophecy: “Miami 2017 (Seen the Lights Go Out on Broadway).” Joel banters with the crowd, reminds them that he’s supposed to mention there’s no smoking, but if they have to that they should “cup it,” before going into “New York State of Mind.” Everybody cheers, they all seem to know the song by now, and they feel the exact same way because he’s singing about how much he loves the town he’s playing in. Then he announces the fourth song as “a brand new thing.” It’s mellow: a soft rock number from a dude who likes to play the tough guy, a tribute to his then-wife Elizabeth Weber that he supposedly didn’t like that much. A few months later, after recording it in a New York City studio with Phil Ramone for his next album, Joel told Phoebe Snow and Linda Ronstadt, both of whom were recording in the same building, that he was thinking of leaving it off. The two women told him he was crazy, that he should keep it. “I guess girls like that song,” Joel gave as his reason for deciding to put “Just the Way You Are” on The Stranger. He eventually released it as the first single off the album when it came out in September of that year.

For an album that would become the one that really made Billy Joel, The Stranger is a little weird, moody and not what you might expect from an album that created a superstar. Even the title is a little off, sharing a name with Albert Camus’s 1942 novel about a man who seems indifferent to everything; he shows little emotion after his mother dies, after he kills a man, and eventually seems to find solace in the fact that he will be put to death for his crime. While there’s no overarching theme that threads Joel’s album together, there is a feeling of discontent laced throughout the whole thing.

We start with grocery-store clerk Anthony saving his pennies for some day in the future. He’s “Movin’ Out” before he has a heart attack (ack, ack, ack), then find out about how the stranger in question is each and every one of us, it’s the secrets we’ll never tell. We listen in on two friends drinking a bottle of white and a bottle of red in an Italian restaurant, discussing how things fell apart for the prom king and queen after high school. Flip the record over to Side B and “Vienna,” one of Joel’s personal favorites, ends so one of his greatest anthems, “Only the Good Die Young,” can begin. As a young Jewish kid who pined over a girl who went to a nearby Catholic school when I was a teenager, I have to admit that the idea of some very Jewish-looking guy trying to convince a girl named Virginia who was shown a statue and told to pray that she should hook up with him because sinning is fun kinda spoke to 15-year-old me. He follows that with another tribute to Weber, who he’d divorce in 1983, with “She’s Always a Woman.”

The Stranger is filled with classics. It’s one of the first albums I can recall hearing as a child. There was a lot of Billy Joel in my life growing up. Yet it’s not my favorite. I do appreciate it, but I always go back to car rides with my dad when I was a kid where we always played An Innocent Man. Little did I know then that Joel’s album was filled with tributes to Motown, Stax and old rock-and-roll of the 1950s; I was too young to understand that so many of his great songs were inspired by everything from Ray Charles to girl groups. I also couldn’t have known that Joel, freshly divorced from Weber, “kind of felt like a teenager again,” because, well, you probably would as well if you were a rich single rock star who was suddenly sleeping with Christie Brinkley.

Even if you could have explained any of that to me when I was four or five, I probably wouldn’t have cared. By that point, Joel already had his hooks in me — that’s how he works. Maybe you’re born a nostalgic, or maybe it’s something that you turn into over time; it’s the great chicken-or-the-egg question that I can’t answer, but I think I can use to explain why I have loved Billy Joel’s music for so long. Listen to any album, and it’s really like sitting at a bar with an old friend: one minute he’s saying something about love, then the next he’s giving you a history lesson of the post-war era by making everything rhyme.

Billy Joel is for the nostalgics and he’s for those who can admit they’re a little corny, and that’s totally fine. He’s also probably the last of his kind: a guy who can get millions of people singing along. There are always going to be great songwriters, sure. But Joel, with his combination of singer and songwriter as well as being a showman, is a rarity in this day and age, and anybody who has gone to see him play his hits to a packed Madison Square Garden or other stadiums over the last few years can attest to the fact that nobody else does it better.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.