The discovery of a Cambrian-era animal fossil has given scientists rare insight into the origin and evolution of our legs.

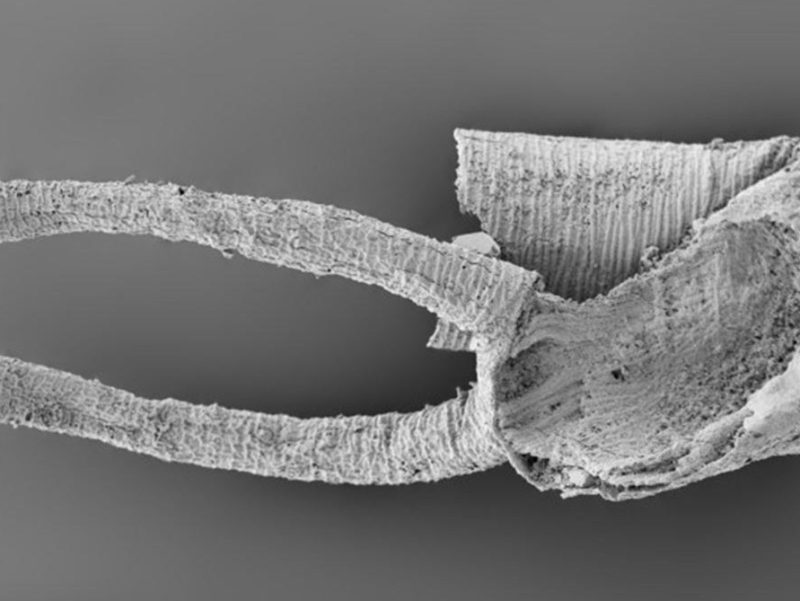

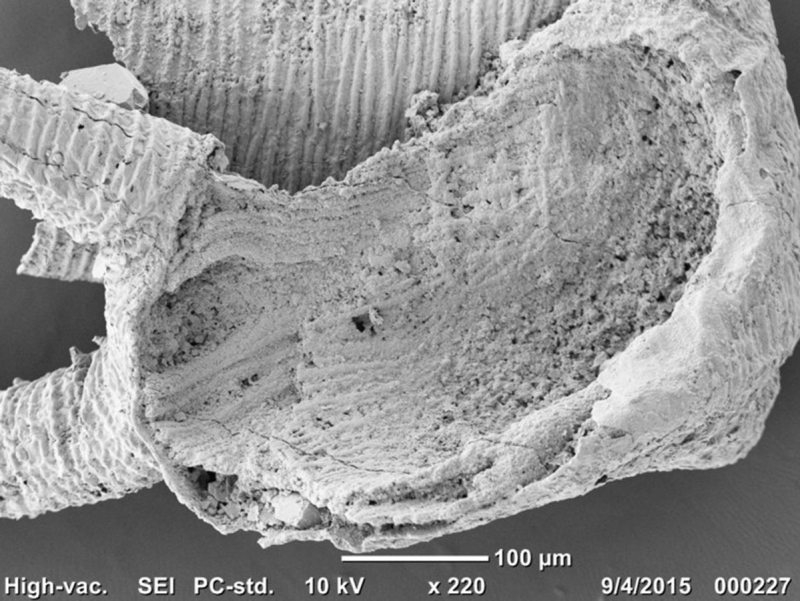

A team of researchers led by Zhang Xiguang found the centimeter-long velvet worm fossil near the Jinsha river, in western China. While complete animals are normally of greater interest to paleontologists, this specimen—a fossilized pair of legs, each ending in three tiny claws—is fascinating for multiple reasons.

Xiguang’s team estimates that it’s around 500 million years old, which makes its state of preservation even more noteworthy; unlike most Cambrian fossils, this specimen’s skin and fibrous muscle tissue are present, which is unheard of among specimens this old. It is, in fact, the oldest specimen with visible muscle tissue on record.

From this, Xiguang and his colleagues reverse-engineered the transition from primordial worms to legged animals. Their findings suggest that legs are the product of a multi-step (if you’ll pardon the pun) evolutionary process in which the muscular architecture of worms progressed over successive generations.

The earliest worms, for example, only had one layer of muscles that limited them to thrashing, jerky motions. A second major generation of ecdysozoan worms had more complicated musculature that could squeeze and expand, allowing them to crawl and burrow. As their muscular systems developed further, they grew legs to accelerate and vary their movement. And between those three advancements were hundreds, if not thousands, of evolutionary dead-ends and misfires.

To read more about this, check out the team’s published article in Biology Letters.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.