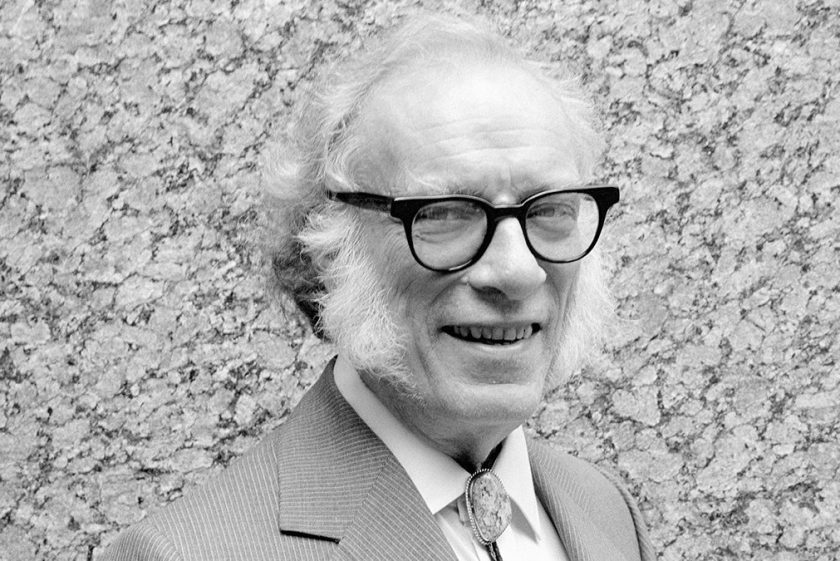

If you’ve ever read anything by Isaac Asimov—say, his Foundation trilogy—within a few pages of the first book you’ll realize that he was a singular talent, the type a publisher might only come across once in a lifetime. (He’s basically to the science fiction genre what Stephen King has been for horror.) And like Jack London, he was highly prolific to the point of disbelief. How could one individual have so many ideas?

Writer and editor Charles Chu set out to explore this question on Medium by leafing through Asimov’s three-volume, posthumously published autobiography, It’s Been a Good Life (edited by Asimov’s wife). RealClearLife has curated our own list of pointers on how to be prolific and never run out of ideas based on Chu’s post.

Learning Is a Lifelong Endeavor

Though Asimov had a Ph.D. in chemistry from Columbia University, that didn’t stop him from being an intellectual sponge long after getting his doctorate. Said Asimov in Good Life:

“I couldn’t possibly write the variety of books I manage to do out of the knowledge I had gained in school alone. I had to keep a program of self-education in process. My library of reference books grew and I found I had to sweat over them in my constant fear that I might misunderstand a point that to someone knowledgeable in the subject would be a ludicrously simple one.”

He also notes that he was a voracious reader. We can’t emphasize this more: reading everything—books, magazines, comic books—is the key to becoming a better writer.

The First Rule of Writer’s Block: There Is No Writer’s Block

Every writer’s been through it: You get about 100 words into a story, and you just want to pick up your computer and throw it out the window. There’s nothing else in your brain; you’ve squeezed out every last droplet of creativity. Asimov’s response to that?

“I don’t stare at blank sheets of paper. I don’t spend days and nights cudgeling a head that is empty of ideas. Instead, I simply leave the novel and go on to any of the dozen other projects that are on tap. I write an editorial, or an essay, or a short story, or work on one of my nonfiction books. By the time I’ve grown tired of these things, my mind has been able to do its proper work and fill up again. I return to my novel and find myself able to write easily once more.”

In short, stimulate your brain with other, like-minded (but dissimilar enough) activities, and you’ll find that, in getting back to those 100 words, you’ll be bringing a fresh set of eyes (and a clear mind) to the work.

Rage Against Your Insecurities

If you’ve ever published any piece of writing, you’ll know the blood, sweat, and tears that went into turning it in to an editor. In the lead-up, you’ll second-guess your word choices, sentence structures, and sources until the piece makes its way into a magazine or online. And then you have to deal with the consequences: Will your reader understand you? Will the response to it be what you wanted it to be? Asimov has this to say:

“The ordinary writer is bound to be assailed by insecurities as he writes. Is the sentence he has just created a sensible one? Is it expressed as well as it might be? Would it sound better if it were written differently? The ordinary writer is therefore always revising, always chopping and changing, always trying on different ways of expressing himself, and, for all I know, never being entirely satisfied.”

Clearly, what he’s saying here runs counterpoint to the usual saying, “you are your own worst editor.” Be the world’s toughest editor to your own stuff, and even if you come out not being satisfied by the product, you’ll at least be aware of the energy and time that went into making it happen.

The Secret of Your Success

Writes Chu: “A struggling writer friend of Asimov’s once asked him, ‘Where do you get your ideas?’ Asimov replied, ‘By thinking and thinking and thinking till I’m ready to kill myself.’”

Now we wouldn’t suggest going quite that far to bring your next idea to fruition, but don’t underestimate the amount of time it’ll take to turn it into a well-constructed story. For example, don’t be afraid to spend weeks or months writing a single paragraph. If it needs to be developed, bolster it with additional research, reading, and thinking.

To read the rest of Chu’s piece on Asimov, click here.

—Will Levith for RealClearLife

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.