Despite the contemporary focus on concussions in football, the fight to make football safer isn’t anything new. That battle is 200 years old.

Despite a decline in concussions this season versus last, many believe the NFL should be doing more (and should’ve been doing more for a long time before that). There’s good reason: players’ lives are at stake.

To that end, players have been retiring earlier in an attempt to avoid becoming a statistic like Junior Seau or Mike Webster. Because concussions and CTE have only recently found their way into the national press, it’s easy to assume that life-threatening (or -ending) injuries like these ones are an aspect of the modern sport. That couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, football injuries and their harmful aftereffects have been in and out of the press since the 19th century.

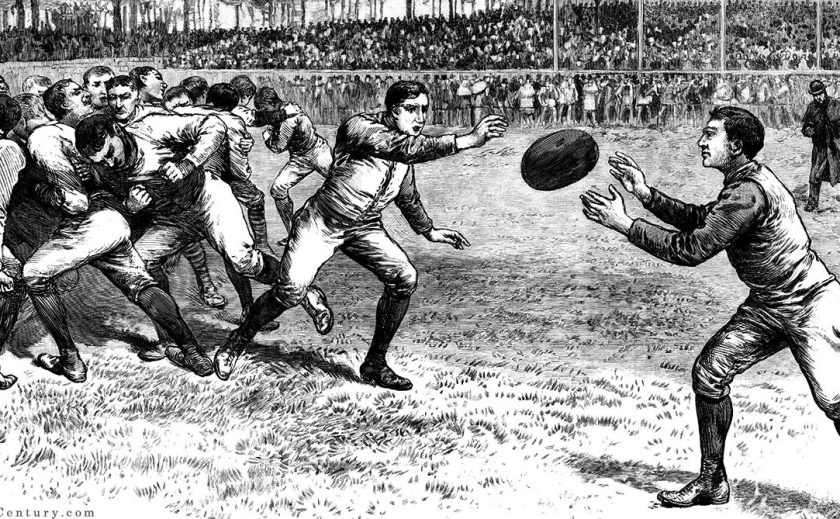

Now, a recently published compendium of articles and images from the sport’s earliest years—1827 to 1898—show that the crusade to make the sport safer (or just ban it entirely) has been around for nearly 200 years.

As part of the Lost Century of Sports Collection, The First Crusade Against Football, edited by Greg Gubi, collects centuries-old media reports on the sport, showing just how brutal and bloody primitive football fields were—and what we can learn from it.

Below are just a few incredible tidbits you’ll find in the book.

Bloody Monday: Long before U2 made Sundays the bloodiest day of the week, colleges across the nation had a reason to call dibs on Mondays. At the beginning of a school term, sophomores would take on freshman in a brutal game of football known as “Bloody Monday.” The event was usually highlighted by rowdy, drunkenness, and life-threatening injuries. The ritual started at Harvard and stuck around until 1860.

Walter Camp: Every footballer should know his name. A player for Yale in the 1870s, he would go on to help bring standards like the line of scrimmage and the quarterback position to the nascent game. He loved the game, but he also had to deal with a growing number of voices speaking out against the sport because of its violent nature. So he pulled a FiveThirtyEight on early opponents (see below).

The Flying Wedge: Invented in 1892, it was an offensive football play, where a ball-carrier would move forward, with a triangular group of defenders on either side. It sounds harmless, but it was actually based on Napoleonic battle tactics. Anyone in its path would suffer severe injury—and sometimes, even death. (It also sounds a hell of a lot like a goal-line stand, but it’s apparently still illegal.)

More Violent Than Boxing?: One New York Times article from 1894 cited in the book, entitled “More Brutal Than Prize Fights,” features a city reverend speaking out against the dangers of football. Notes the reverend: “‘The gladiatorial shows of Rome, the bull-fights of Spain, and our prize-fights are refinements, compared with the football brutality of today.”

Camp’s Survey: Two years after the Flying Wedge brought a sea of blood across the country, Walter Camp went the data-driven (i.e. FiveThirtyEight) route to explain the game’s ins and outs to the average person. To do this, he polled former players and administrators about the game’s role in their lives (negative/positive), as well as injuries they may have sustained. That Camp was the report’s lone editor calls the facts into question, but it was the first of its kind. The entirety of Camp’s report has been republished in The First Crusade.

To order a copy, click here.

—Will Levith for RealClearLife

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.